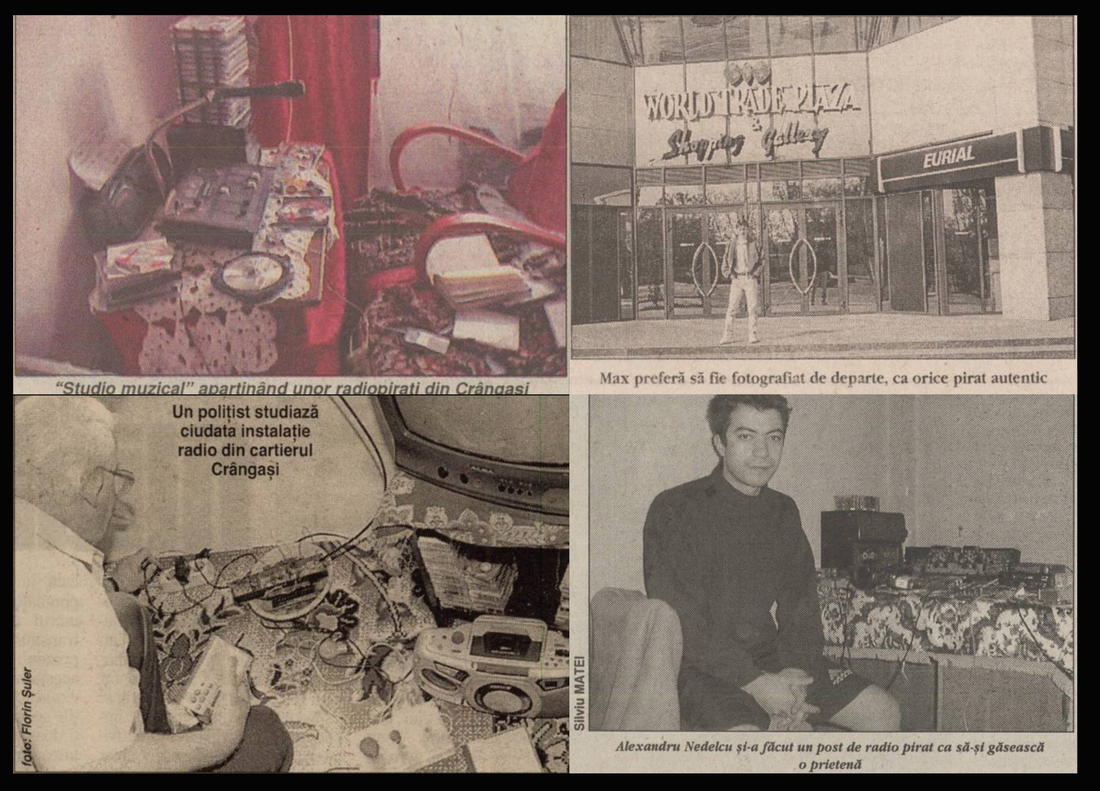

The relationship between pirate radio and the state was deeply ambiguous. On paper, the law was clear and severe. The 1992 Audiovisual Law stipulated prison sentences from six months to two years for unlicensed broadcasting. In practice, enforcement was inconsistent, chaotic, full of gaps. Almost all testimonies converge on the same paradox: pirate radios were shut down and equipment confiscated almost exclusively following specific complaints—from licensed stations, jammed institutions, and the like. There were no systematic, proactive eradication campaigns. There was tacit tolerance, sometimes bordering on complicity, until someone “got upset” or interference became too obvious and inconvenient.

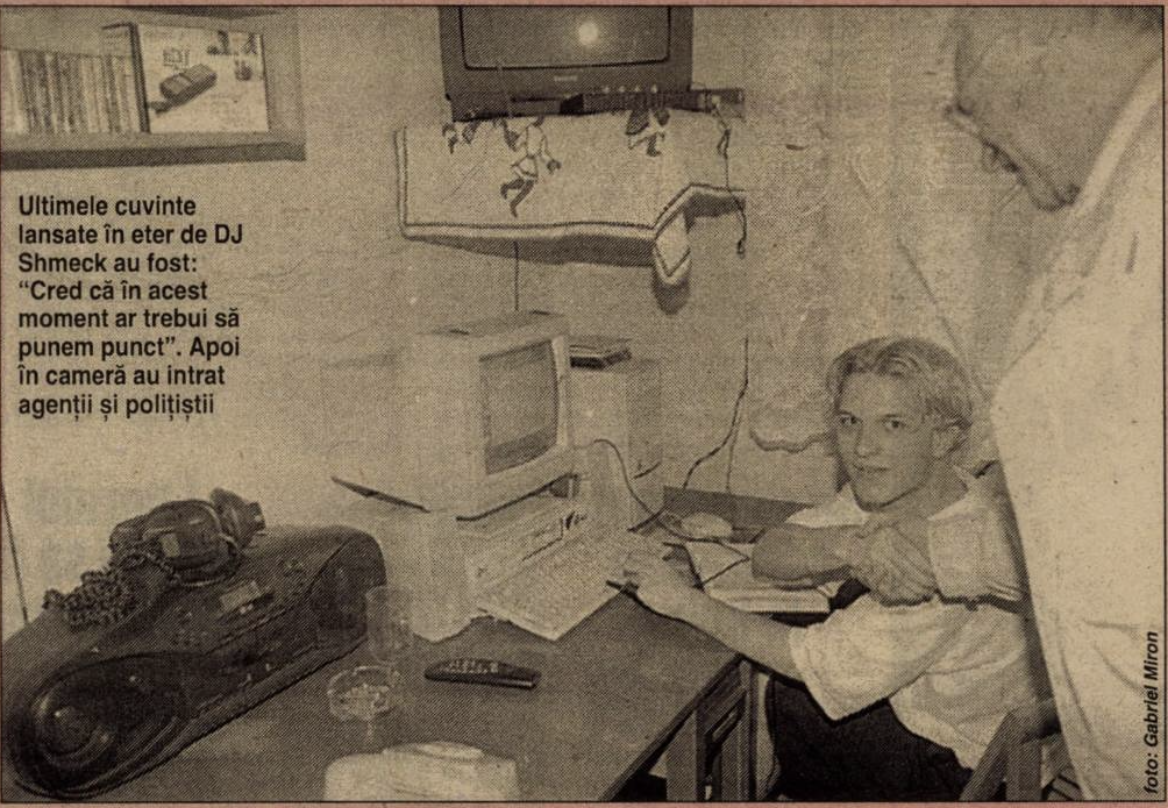

DJ Zet articulates this perception clearly: “We knew it was illegal, but we didn’t feel like we were doing something wrong. We felt we were filling a gap.” That sentence summarizes pirate radio’s practical, not ideological ethic: not a declared rebellion against the system, but a response to a real need, an institutional void. He describes the ambivalent mechanics of the “hunt”: “Dangerous? It wasn’t dangerous except for being illegal. Our biggest fear was that they’d come and confiscate the equipment. They knew about you, but if you didn’t bother anyone, they didn’t really come. When they went to one station, that one would warn everyone: ‘Guys, there’s a raid… shut down.’ And we’d stop broadcasting for a week.” This temporary suspension was part of the game—a tactical pause, a temporary retreat in a war of attrition with a predictable bureaucratic adversary.

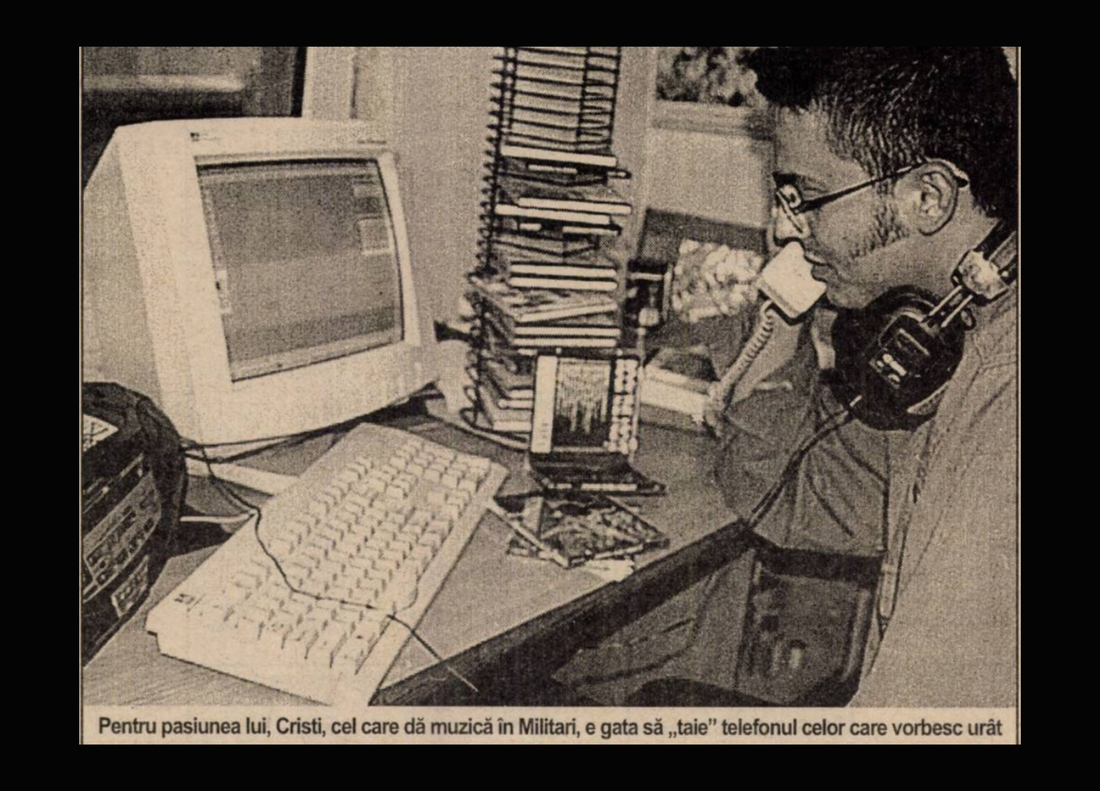

Sometimes, however, interference had serious consequences, exposing the state’s shocking vulnerability. In 2001, the Special Telecommunications Service was reportedly “inoperable for a month,” blocked by a clandestine operator broadcasting on its secret channels “while looking for a girlfriend.” This absurd-sounding incident is a perfect indicator of the fragility of the post-communist state’s infrastructure which was underfunded, technologically outdated. The fact that a neighbourhood kid could jam vital government communications says much about pirate ingenuity, but also about a state still learning how to function.

The end of pirate radio did not come through a decisive state victory over anarchy, nor through coherent media reform. It came through slow exhaustion. Through forced professionalization. Through the relocation of cultural infrastructure. Through a complex mix of fatigue, accumulated fear, pragmatism, and above all, radical technological transformation. Pirate radios were not defeated in an epic battle; they were absorbed, gradually emptied of their original meaning, and eventually replaced. For DJ Zet, the transition moment is not dramatic, but a sober recognition of a new reality: “At some point, it no longer made sense. It wasn’t the same. Either you went legal or you moved online. FM had become too risky and too empty.” His statement perfectly captures the end of an era. Not a spectacular collapse, but a slow, almost natural withdrawal from a space that no longer offered what it once had: opportunity, adrenaline, utility.

After 2003-2004, institutional pressure visibly increased. The National Audiovisual Council consolidated its authority, IGCTI became ANCOM, legislation clarified (even if it remained problematic), and tacit tolerance gradually turned into systematic intervention. The press increasingly noted “annihilations,” “equipment seizures,” “criminal files” against pirates.

Libertatea and

România Liberă published punitive articles about “the last pirates,” about “kids playing radio,” sublimating threats to national security. The tone was no longer ambiguous or curious, but condemnatory.

At the same time, something far more important than bureaucratic repression was happening: pirate radio was rapidly losing its primary social function. Broadband internet became accessible in cities. MP3s circulated freely. Specialized forums, messengers, later early social and streaming platforms offered something FM could no longer provide: music access without risk, without physical antennas, without fines, without fear of police visits. Sound no longer needed physical ether to circulate. Community no longer had to be geographically proximate; it could be interest-based, dispersed. Exactly what had once been pirate radio’s supreme strength, locality, physical proximity, shared risk, transmitter materiality, suddenly became a disadvantage, an unnecessary burden. DJ Zet speaks explicitly about this threshold of awareness: “When I saw you could reach people without risking anything, without hiding, without carrying transmitters, it was clear it was over.” This is not a statement of defeat, but of realistic adaptation.

Pirate radio as an FM phenomenon does not die. It simply moves. First online, then onto social platforms, sometimes keeping the name, sometimes the community, but permanently losing its aura as an act of physical, territorial resistance. Today,

Radio Pro-B continues to broadcast from the Romanian online space.