After a history of institutionalised racism, it was only 35 years ago that the Roma were recognised, for the first time in Romania, as a national minority with all the cultural rights associated with this status. However, they still do not fully enjoy these rights in social practice. Among other deprivations of cultural rights is the absence of a museum of Roma culture and history, a fundamental reparatory institution for the preservation and development of Roma cultural memory, part of transitional justice.

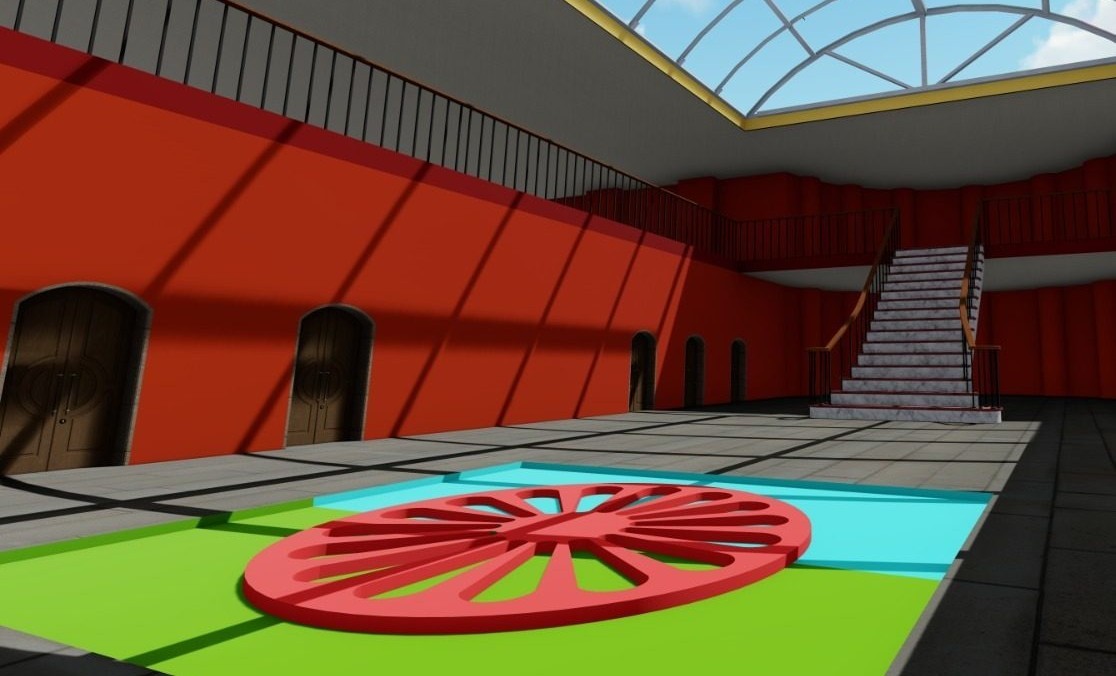

In the absence of a physical public museum, we considered it very important to create

a virtual museum of Romani culture, which can be visited by both Roma and non-Roma in Romania, as well as by Roma and non-Roma from anywhere in the world, which makes it, at least in terms of accessibility, even more important than a physical museum. We achieved this between 2021 and 2022, as part of the "We Can Do More Together" project, in which our association, „Amare Rromentza” Roma Centre, was the partner responsible for creating this virtual museum of Romani culture.

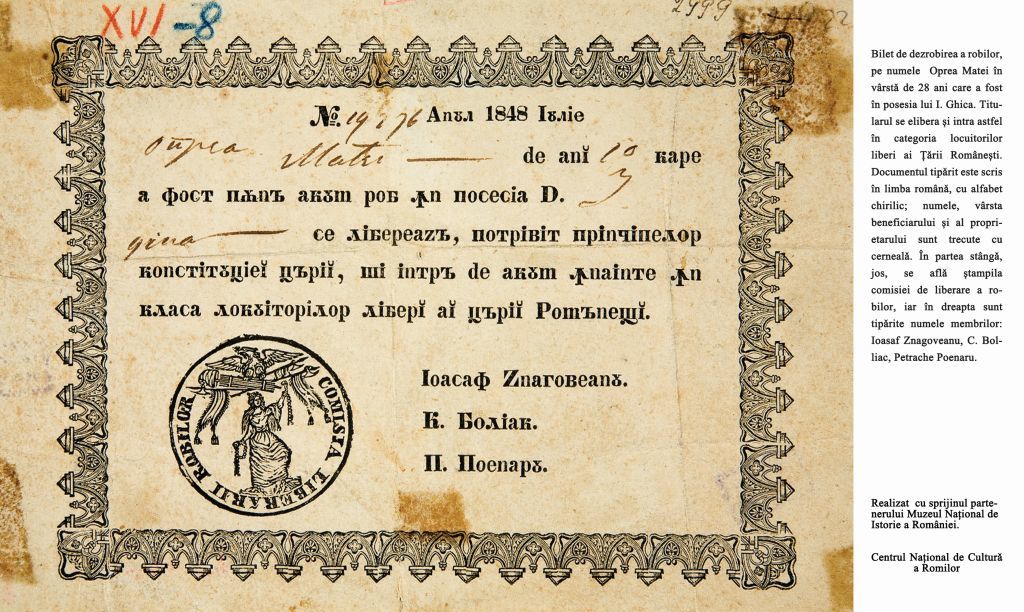

The museum reflects both the values of traditional and modern Romani culture and the tragic history of the Romani in Romania (slavery, Holocaust, cultural ethnocide during the socialist regime, contemporary anti-Romani racism), both the ancestral Romani ethnotype and its modernisation process, both the Romanipen in absolute terms and the culture of internalised stigma, both the historical process of civic and cultural emancipation of the Roma after their liberation from slavery and up to the present day, and the projection of the Roma into the future or the process of building a non-territorial and cross-border Romani nation.

All components of the museum are presented through a soundscape, including voices reading historical documents and music, through minimalist graphics representing symbols from Roma history and culture that induce empathy in the visitor, through the emotion associated with each virtual space, as well as through images of historical documents, period photographs and contemporary photographs/films that reconstruct the moment or the element being explored, with a view to providing a deep understanding of Roma history and culture. Navigating the virtual museum space allows visitors to enjoy an immersive emotional experience.

The virtual spaces are not classic museum halls, but are located outdoors, in different landscapes, adapted to the content of each topic addressed, and have the name/message of each written on a gate adapted to the content of that virtual space. In each of these spaces, visitors participate in the virtual reality created through thematic animations and view 3D, 2D or 360-degree images with objects and documentary films related to the period and/or theme of that virtual space. Visitors are accompanied by the voice of the museum guide, who provides information on the topics covered in each virtual space. The museum guide is available in three languages: Romanian, Romani and English, and visitors can choose their preferred language.

Each virtual space contains the following sections: Virtual Reality, Photographs, Video and "Secret Room", which visitors can access by answering a simple question about Roma culture and/or history. In this room, visitors will find several historical documents, photographs, films about the Roma, books and useful links.

The

virtual museum is accessible on any computer and includes – in the Public area – visiting the rooms of the virtual museum, accessing content (images, films, audio files from each space) and viewing parts of the content using virtual reality headsets. In the Private area, the museum offers: ability to edit content (continuous updating, adding information); organisation of online Roma cultural events (exhibitions, conferences, scientific sessions, concerts, theatre performances, film screenings, courses, talk shows etc.).