Eastern Bloc states adopted widely divergent policies toward their Roma communities, ranging from recognition to outright erasure. Bulgaria forced Muslim Roma and Turks to adopt Christian or Bulgarian names and banned Romani musical forms like the

kyuchek.

Czechoslovakia went beyond cultural erasure, promoting the sterilization of Romani women in exchange for cash rewards.

Meanwhile, Yugoslavia took the opposite course, allowing Romani political and cultural life to flourish and even adopting the ethnonym “Roma” in official discourse.

Hungary, too, granted official recognition in 1984.

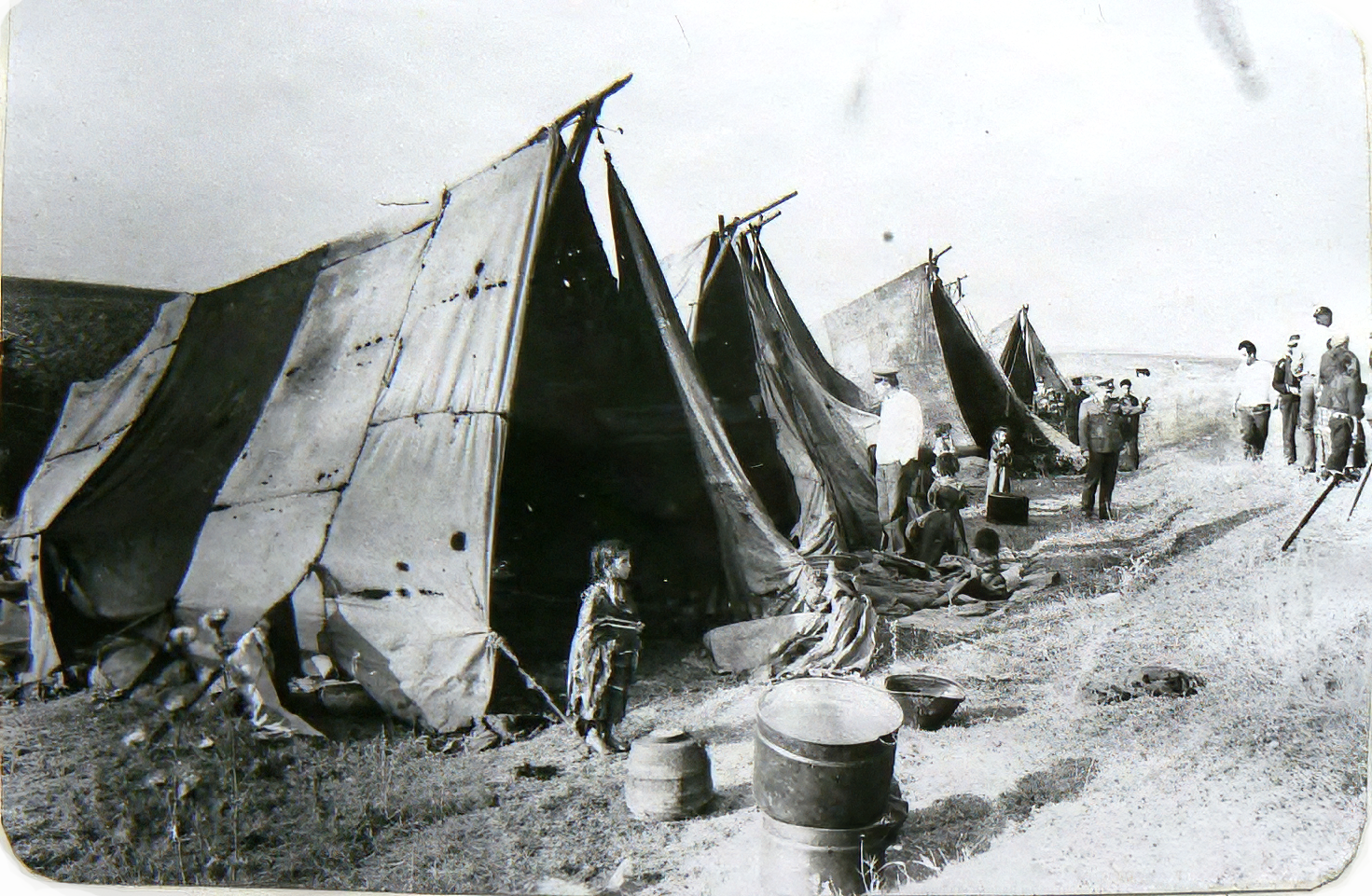

Police raid an encampment of tent-dwelling Roma, 1977. Source: ANIC(2).

Romania’s undeclared policy fell somewhere in between these extremes: it denied the existence of a Romani minority and criminalized many traditional trades, even as it exploited and celebrated the musical skill of

lăutari for the propagandistic aims of Party and Leader. A secret report from November 1977 cites Ceaușescu ordering “vigorous measures … to liquidate the nomadic phenomenon among the Gypsy population,” using the alleged criminality of the Roma to justify accelerated policies of forced sedentarization.

Echoing the fascist discourse of the 1940s Antonescu regime, the report claims that the “Gypsy population” has a “parasitic conception of life and [a] disregard for the rules of social coexistence” and survives on “theft, robbery, begging, cheating, [and] fortune-telling,” supposedly accounting for an implausible 13% of all crime annually.

As settled Roma whose privileged profession allowed an escape from the draconian employment decree through participation in state folklore ensembles,

lăutari were largely unaffected by these policies. Censorship posed a far greater threat: performing the wrong repertoire for the wrong crowd could have real consequences, and songs circulated in private “underground” contexts often carried messages at odds with official narratives and ideology. One prominent example is the song “Bălălău” (Simpleton), first recorded by Marcel Budala in 1970 as simply “

Hora lăutărească” whose popular underground lyrics began “Simpleton, mama’s boy / The whores ate up your money / Let them eat my money, mama / For their lips were sweet. / Come, come, simpleton / Stop your drinking, my boy.” A thinly veiled reference to Ceaușescu’s alcoholic son, Nicu, the song became a common request in Romanian taverns of the 1970s. Gicu Petrache recalls:

“Eventually they banned it from being performed at gigs, weddings, everywhere, and I really can’t blame them. Everyone sang it as they liked, and they’d even make references to the leadership, the Party: ‘Simpleton from Scornicești [Ceaușescu’s home village] / Simpleton from Scornicești / If you saw him you’d go mad / He’s got money and a car’… Who was the simpleton from Scornicești? You didn’t have to be a genius to figure it out.”

Other musicians told me of singers hauled off and beaten by the police for performing “Bălălău,” yet its notoriety only fueled its appeal. In response, the authorities promoted “clean” versions in order to neutralize its subversive power. Folklore singer Ion Dolanescu’s 1973 radio performance “

Bălălău, băiatul mamii” was one such attempt, and

lăutar diva Gabi Luncă went even further with “

Pe drumul de la Buzău” (On the road from Buzău) that same year, transforming it into the harmless tale of a cheerful roadside singer. The “Bălălău” melody proved so infectious that it began a circuitous journey across Europe, spawning cover after cover before looping back to Romania. It first resurfaced in Yugoslavia as Darko Domijan’s “

Zingarella” (Gypsy Girl, 1982), then in Bulgaria as Stefka Berova and Iordan Marchinkov’s “

Магдалена” (Magdalena, 1984), and later in France, where Enrico Macias recorded his own “

Zingarella” (1988), in turn inspiring Romanian pop singer Alexandru Jula’s down-tempo ballad “

Mi-ai adus iar primăvara” (You Brought Spring Back to Me, 1986).

--crop.jpg)