“Song of Romania”, for instance, was a political festival, in the sense that it incorporated a set of politically organized performative and celebratory events, mass assemblies and artistic competitions, with the purpose of disseminating political symbols of the socialist and national ideology of communist regime. It did not have the sole purpose of providing political legitimacy, as there were other means to achieve this goal.

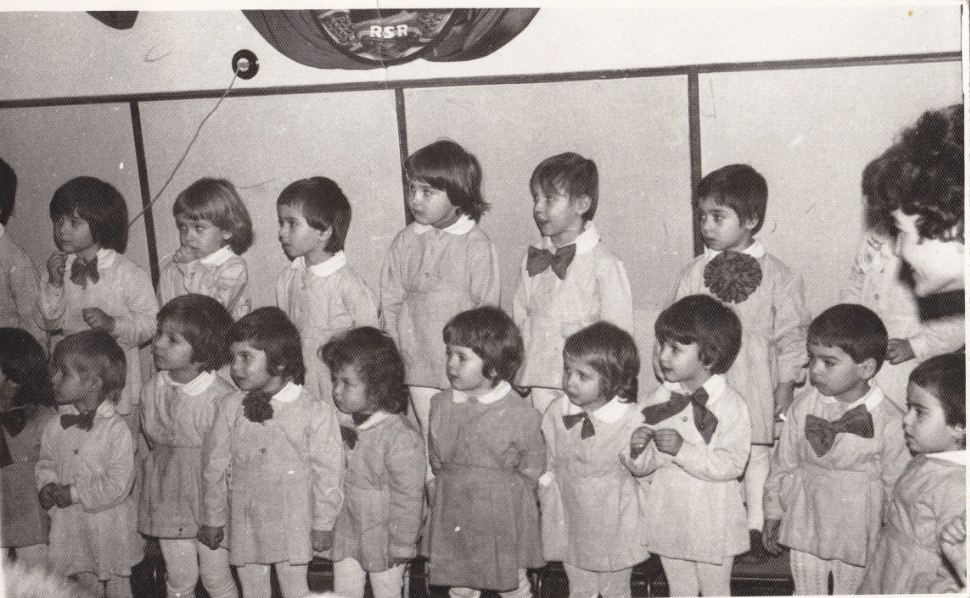

By using the pretext of constructing a new culture, the festival aimed at creating a new set of social relations, at inducing a shift in social status for intellectuals and professional artists, in order to avoid any critique or resistance from the latter. In doing so, the festival became the ideal framework for bringing together two main components of what was intended to be the socialist order of Romania under Dej and Ceaușescu: the masses and the Party/later on the leader. Political rituals were used extensively to mark this dissociation and traditional aspects of festivals, such as the temporary reversed social order were reinterpreted, in order to fit in, for example, with Ceaușescu’s personality cult. The ultimate aim, although never officially recognized, was to create a new mass identity, in which individual values were left aside. Mass rallies at the ending festivities for each edition of the festivals proved to be an ideal source for exploring the functions of political rituals for the case of Romania, in particular, and for modern societies, in general.

The official image is, nevertheless, transformed if one construes the unexplored side of the festivals: ordinary people’s response to them. Most people did not have any particular reaction, as they perceived the festivals as something normal for the respective period. Moreover, depending on their social, age and professional status, as well as on their intellectual background and access to information, people responded in various ways. They either participated in them, without getting involved, or regarded them as a formal activity, part of everyday responsibilities. They also perceived them as an occasion to be promoted, or to witness a change in social status. The festivals themselves became an independent structure, an alternative plan, which needed to be fulfilled similarly to economic plans in industry and agriculture.

Consequently it can be implied that they led to the appearance of new social relations and changes in social status for awarded participants, or for organizers. Workers and peasants suddenly found themselves applauded and praised as innovating and representative artists, and could afford financial and material advantages which were normally out of their reach. Activists organizing various competitions within the festival managed to interrelate with economic directors, in order to insure their funding. Although official sources claim that special funds were attributed to the proceedings of the festival, present interviews with organizers suggest a different version. Further inquiry still needs to be undertaken regarding this particular aspect, but the research conducted so far on interviewees proves to be a promising starting point for revealing an entire alternative social structure, left outside official recordings.

Furthermore, political festivals can prove insightful when discussing the complex issue of how people remember communism. Historical memory and collective memories intermingle with personal memories from case to case to offer various narrative discourses. Beyond this narrative variety lies a set of patterns, out of which the most important one is the ambiguity in people’s recollections of the festivals. Most interviewees have first mentioned their negative sides, only to stress the positive aspects later on, in an “it wasn’t that bad” type of discourse. Two main explanations can account for this. On the one hand, the festivals comprised so many activities that, in the end, they did not take over ordinary course of events, they simply integrated into them. Despite official claims, political control varied from local levels to the national level and to that of Bucharest, allowing people to modify official requirements according to their own interests and abilities.

Moreover, 1989 marked a radical political rupture with the past, at least at the official level. This meant that ordinary people had to abruptly modify their set of values and their socially accepted discursive code. Whereas before 1989 there was a code of publicly accepted discourses and private opinions which had to remain private, after 1989, most people retained only this duality but completely changed the corpus of “publicly accepted” versus “privately accepted” statements.

*This article is part of the project The Sonic Turn, co-financed by

AFCN. The project does not necessarily represent the position of the Administration of the National Cultural Fund. AFCN is not responsible for the content of the project or the way its results may be used. These are entirely the responsibility of the funding beneficiary.