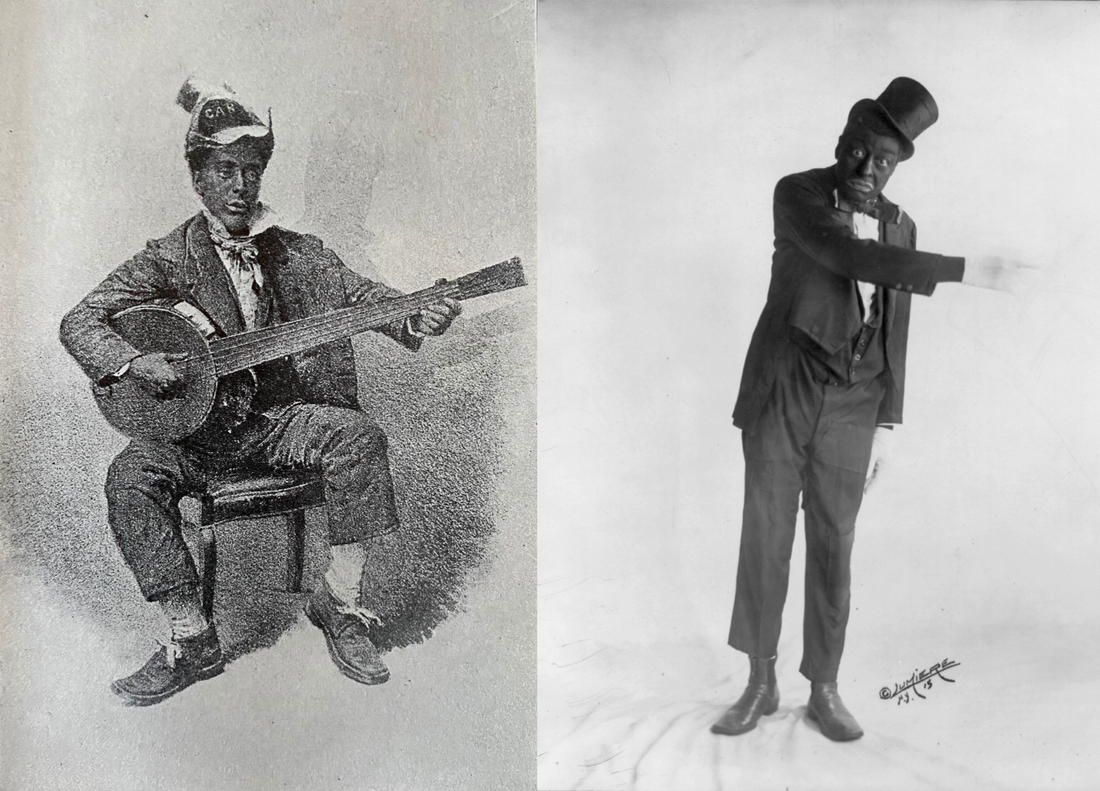

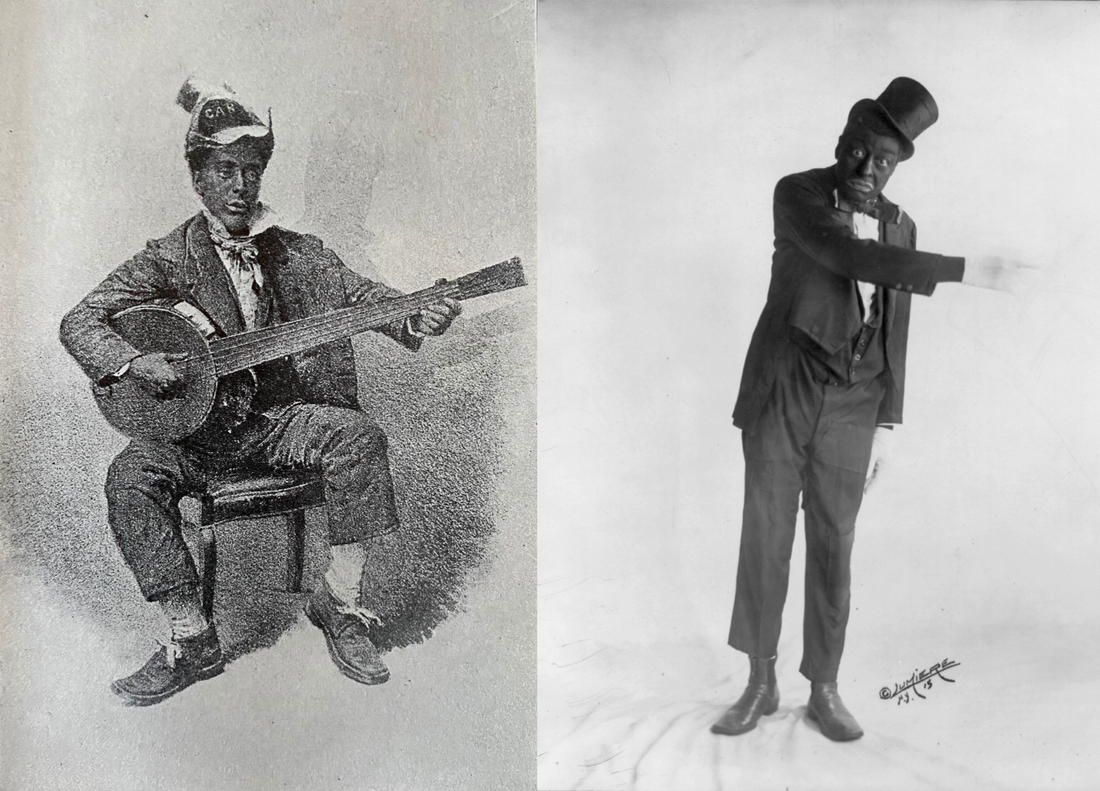

Edwin Pearce Christy (left), a Blackface minstrelsy star of the 19th century, and Black Bahamian immigrant Bert Williams (right)

Despite periodic proclamations that the U.S. is “a nation of immigrants”, prevailing attitudes toward immigrants have fallen into three broad categories that have waxed and waned in relation to one another since the foundation of the country:

Anglo-assimilation. Immigrants should make themselves like the descendants of the British colonists of the 17th century, adopting their language, customs, and attitudes as quickly as possible, and dispensing with the vestiges of those they brought from home, thereby becoming American.

The Melting Pot. New arrivals with their own traditions and values will settle alongside native-born people, and over time, each will take on aspects of each other’s ways of being. Eventually, over generations, the blurred differences between them will result in Americanness.

Cultural plurality (multiculturalism). Cultural groups will live side by side, harmlessly retaining their own cultural specificities. Americanness will result from the creation of a functioning society by people with many ways of being.

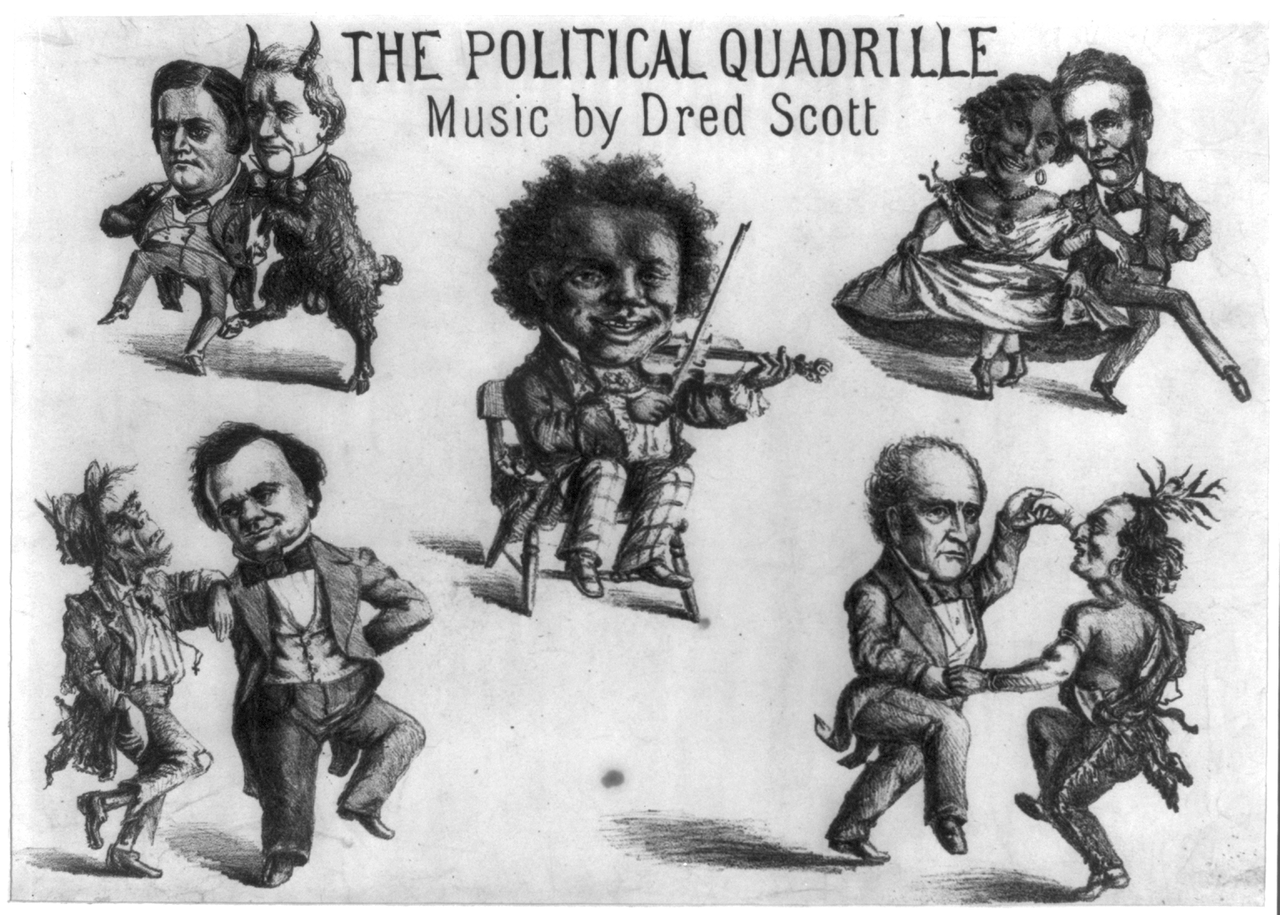

Power dynamics were built into voting rights laws established immediately after the Constitution’s ratification. In 1790, male new arrivals who were “free” and “White” and “of good character” could vote immediately upon arrival. In some states, immigrants were initially required to own land in order to vote. Five years later, the law was revised to impose a five-year waiting period. Just three years after that, the requirement was extended to fourteen years. By 1802, however, this was deemed draconian, and the waiting period was reduced back to five years. This initial back-and-forth movement in the distribution of democratic power, along with the outright disenfranchisement of Black, Native, and female people was the baseline of the ongoing struggle of the dominant powers to retain “in” and “out” groups, while indicating a commitment to Democratic ideals embodied in the relatively egalitarian kinglessness of the Constitution and Jefferson’s assertion that “it is self-evident that all [people] are created equal.”

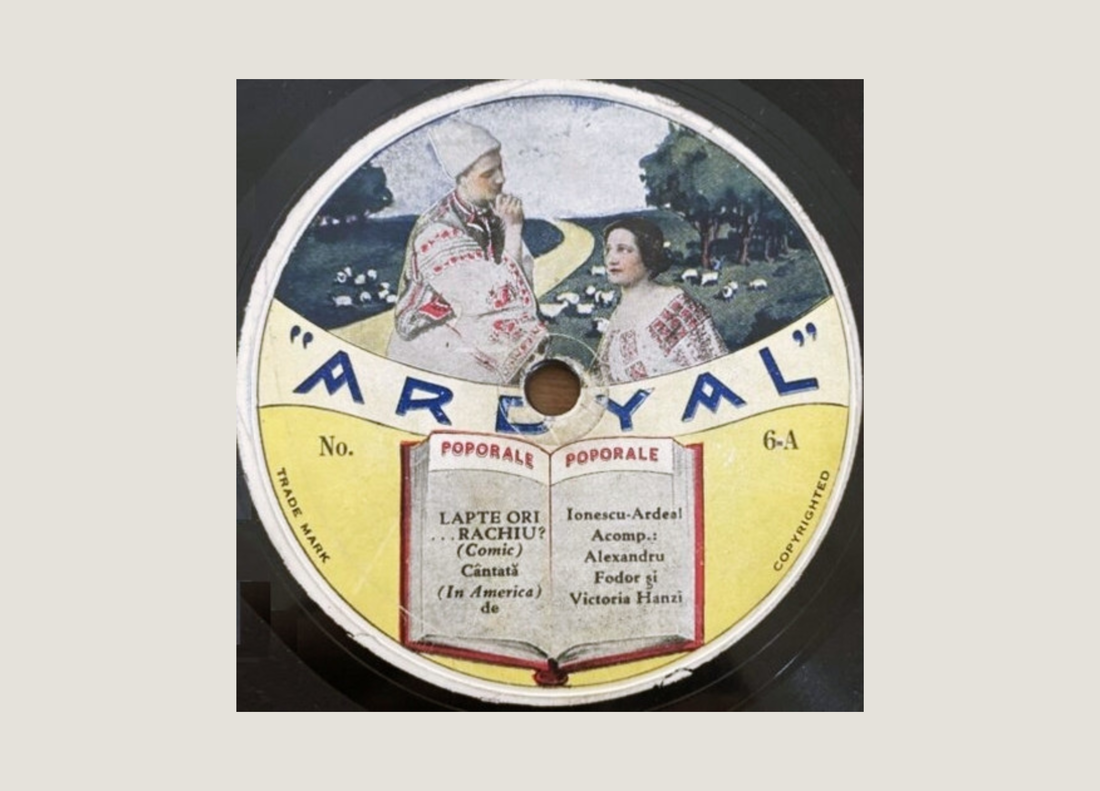

In the early 1920s, an American hit song was recorded by at least seven different performers in both the U.S. and U.K. expressing widespread anxiety about the perception of a threatening demographic shift. Its U.S. version began:

Columbus discovered America in 1492 / Then came the English and the French, the Scotsman, and the Jew / Then came the Dutch [German] and the Irishman to help the country grow / And still they keep on coming, and now everywhere you go / It’s the Argentines and the Portuguese, the Armenians, and the Greeks. Later verses portray the exotic, dark-eyed newcomers as rent collectors, drivers of the best cars, and as overcrowding the subway. The new immigrants were described as both as a bit repulsive and replacing “us.” One verse conveys sexual anxiety about women choosing them as partners and bearing their children. Later, a grudging admiration is shown for the earnestness of the new arrivals’ determination to become American:

They don’t know the language, they don’t know the law / Yet they vote in the Country of the Free / Now the funny thing, when we start to sing / “My Country ’Tis of Thee” / None of us know the words but the Argentines, and the Portuguese, and the Greeks.

In fact, the North American continent was still divided among three Empires in the 18th century—Spanish, French, and English—of whom two were Catholic. Among British settler-colonials, Catholicism was viewed as a significant problem. The 1774 British Quebec Act which gave some rights to French Catholics in British Canada was among the instigating factors of the American Revolution. “Papists” were disenfranchised from voting until the Revolutionary War. Jews, meanwhile, were banned from New France and much of the Spanish territories of North America, but Jewish congregations, derived initially in large part from small Sephardic populations originating in Holland, were established in twelve of the thirteen British colonies. By the middle of the 19th century, restrictions from holding public office and suffrage without a public declaration of faith in the Trinity were repealed gradually, state-by-state, with equal political rights established in the overwhelming majority of the country. Anti-semitism became a more significant problem in the 19th century when Jews from the Prussian and Austro-Hungarian Empires arrived en masse. Religious freedom and the separation of church and state remain more an ideal than a fact.

“Mohammedans” were a tiny minority of immigrants and remained largely covert. Approximately 100,000 Ottoman Muslims arrived between 1820 and 1920, but the overwhelming majority came in the first two decades of the 20th century. It was widely known among them that they stood a better chance at entry through the port of Boston than New York, where they were routinely turned away. A Turkish community had been established in and around Peabody, Massachusetts in the early 20th century, but they found America so inhospitable that they largely returned home in the late 1920s. The first Syrians to arrive in 1878 were the subject of immense curiosity, having come from the Holy Land, and were welcomed as highly educated Christians. But two decades later, Syrians’ racial status as “White” or “non-White,” affecting their petitions for citizenship among other legal rights, was called into question in a series of court cases, during the period 1907-1915. Their “Whiteness” was finally legally established not on visible appearance but on an invisible shared Christian cultural heritage.

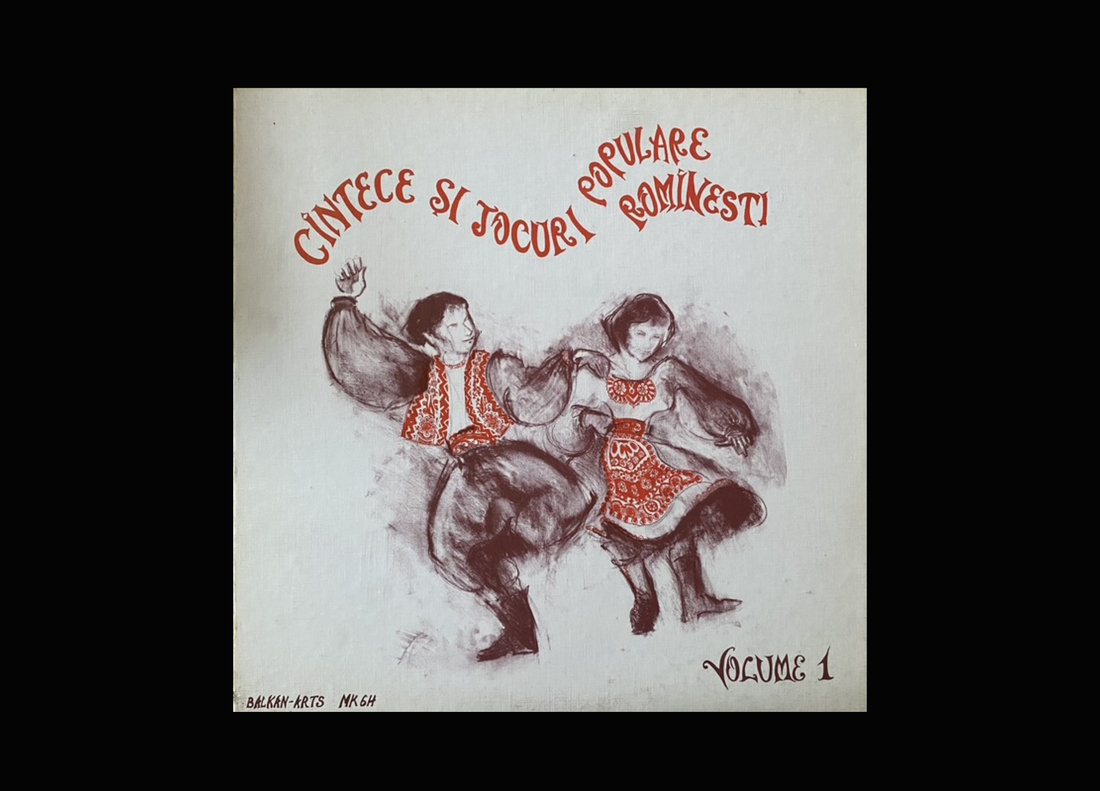

Before the American Revolution, the dominant powers in Pennsylvania were Quakers, who were pacifists and therefore could not wage war on the native people of the western frontier. The Presbyterian Scots who had settled in the Ulster region of Ireland had a reputation as hardy and willing to fight, so 100,000 of them were encouraged to migrate and make their way west, where many settled in the Appalachian mountains, retaining a dismissive attitude toward the earlier colonialists on the relatively cosmopolitan east coast. The Scots-Irish culturally conservative adherence to “the old ways” and ability to survive in the difficult terrain became linked to a “

God, guts, and guns” mountaineer stereotype that was subsequently embraced by a stream culture as especially American. Similarly, images of the 19th century westward “pioneer settler” expansion into the plains and beyond became associated with cowboys, denim, and the gold rush. The elements of the hillbilly image and the cowboy image were then fused and marketed in the middle of the 20th century as “Country-Western” music.

Between 1840 and 1900, five million German speakers arrived in the U.S., and by 1900,

4% of the total population of the U.S. was German-speaking. Among them were thousands of members of a religious order founded in Switzerland, whose descendants continue to this day to speak German and refuse assimilation, rejecting consumerism, individualism, and post-industrial technology. While referring to all outsiders generically as English, they live, dress, practice their faith, and organize socially much as they did nearly 300 years ago. When a wave of three million Irish Catholics arrived in the period 1840 to 1890, the established Protestant power structures reacted with violent nativism. In the major port city of Baltimore, Maryland, for instance, where Catholicism had been historically tolerated, nativists employed street gangs to terrorize immigrants and instigated citywide election-day riots from 1854 to 1858, resulting in hours of open gunfire and victories for the nativists.

Meanwhile, through the 18th and 19th centuries, the genocide of Native Americans killed 96% of the indigenous people. As Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote in his 1963 book Why We Can’t Wait, “Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race.” He went on to point out that Americans had continued to celebrate the genocide in its myths. During the decade following World War II, a third of Hollywood’s total cinematic output were Westerns that endlessly repeated the image of the heroic settler in conflict with the forces of nature of which one was the people who lived there.