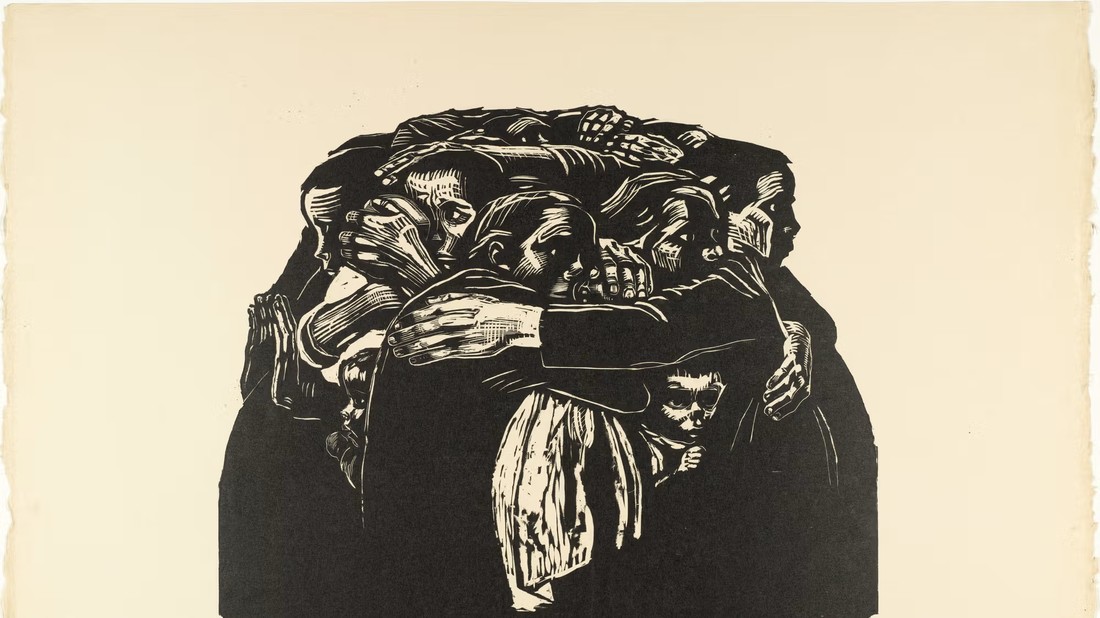

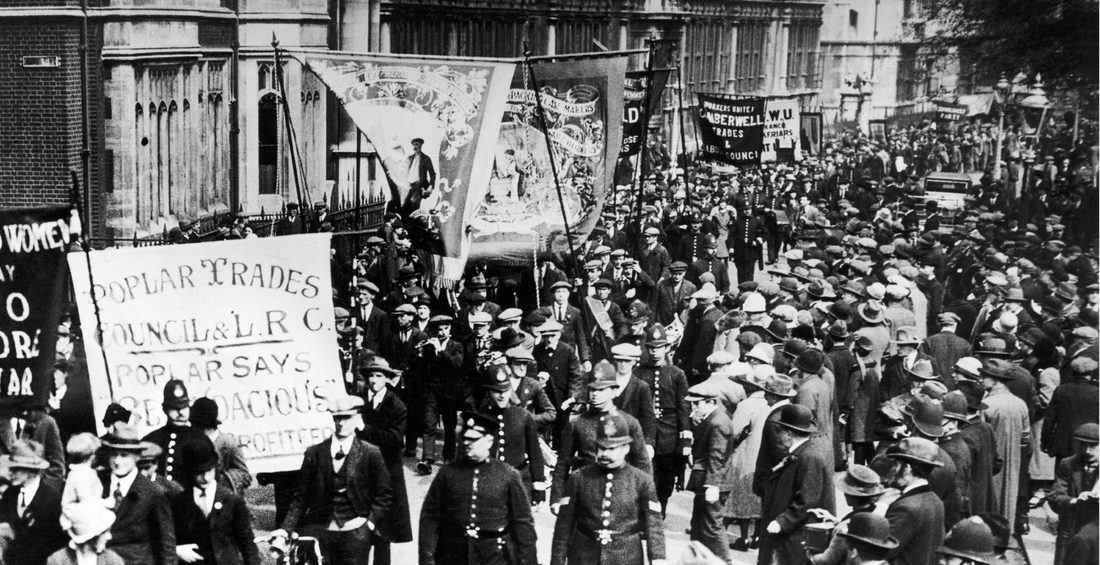

I will go with his suggestion and place academia as a potential force of resistance. And I also add the arts as an important learned practice to this freedom force. The artist, whose anarchic creativity will have saved them from subservience too, can contribute to the performance of anti-servitude as anti-fascism, through a sensory-knowledge practice that generates the responsibility of resonance: the understanding of our generative role in what we see and hear and how we sense ourselves in these perceptions as beings-with, inspiring new ways to move together. This all assumes of course that the academic and the artist are willing to take on their role as resistance fighters, and that they are trusted, in their own separate hierarchy and status, by the worker, which presents a small contradiction. But still we can hope that they do, and that their choreography will be accepted and has the power to enable resistance. And that is where the authoritarian is cunning. They know to control and defund academic knowledge and art, portraying it as useless, elitist, another enemy and scapegoat rather than a body with the means to perform the necessary disobedience.

Contemporary, publicly funded, art has to serve the people while defining what that is. The idea is that your gallery visit should satisfy you. That it should live up to your expectations rather than provoking new ones; such as providing cause to examine your servitude in a neo-liberal context and develop the desire to escape it. And so art and knowledge is censored and defunded in an attempt to curtail the unexpected and regain ground and absolute control. The aim is to give the museum’s visitor a sense of choice, while controlling them into acquiescence with an economic, and socio-political status quo that makes them impotent, humiliated, frustrated but with no means to understand the source of this discomfort and pain. While this might sound like a conspiracy theory, the current moves of the Trump administration, for example, against science, against universities and most importantly for this discussion, against cultural institutions like the Smithsonian Institute or the John F. Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts,

prove otherwise. Other examples are more subtle, maybe even unnoticeable: small conformities, acts of pre-emptive self-censorship, outright compliance absorbed into an overall aesthetics, into habit or a sense of responsible agency, simplicity and populism for the good of the public visitor, who is humiliated a second time by the suggestion that he would not understand anyway. Refuelling the impotence that drives the chant, rather than providing the condition for another tune.

The relationship between knowledge, aesthetics and populist authoritarianism is historic and powerful. And so I want to go back, to revisit the possibility of sound to perform a resisting collective. To enable us to merely become willing to be free.