“The Gypsies played manele with feverish abandon, the rouged ladies sighed, and the boyars sat on carpets drinking vodka from the shoes of their lovers, hurling their fezzes into the air and kissing the lăutari”;

This nostalgic vignette of a party among rural noblemen in Ottoman-era Moldova published in 1852 by poet Alecu Russo represents the earliest known reference to the

manea in Romanian literature. Russo would revisit the imagined scene in his 1855

Amintiri (Memories), specifying that the Romani

lăutari performed “sweet

manele, comforting

manele, and painful, heartbreaking

manele”.

Over the next seventy years,

manele are frequently evoked in the Romanian press and literature alongside fezzes, turbans, hookahs, and rugs as a symbol of the Orient—whether a romanticized past or an exoticized present.

The

manea enjoyed by Turks, Greeks, Bulgarians, and boyars alike is portrayed as a “Turkish song expressing melancholy and love”

—“long and plaintive”

, “monotonous”

, “soft and broad”

“its elongated notes more a lament than a melody”

. This

manea bears little resemblance to the one known today: there is no mention of belly dancing, drums, or even rhythm itself. It was not a dance, but a kind of cântec de jale—a song of lamentation whose lines often began with the exclamation “Of!”, much like “Aman!” in Greek and Turkish folk song. For some, this

manea was emblematic of a shared post-Ottoman heritage linking Romania with its Balkan neighbors. In 1931, the poet and cultural official Emanoil Bucuța recalled a Turkish diplomat in Bucharest who, upon hearing a lăutar’s mournful tune, recognized it as an Anatolian melody:

“Our old song was nothing more than a manea that had wandered across the Danube in a time when there were no border posts to halt it.”

The word

manea—and, it seems, the song form referenced in 19th century Romania, comes from the Turkish

mânî (plural

mânîler), a widespread form of folk poetry usually comprised of four-line stanzas in an AABA rhyme scheme.

Mânîler are poems recited or sung in everyday life—from work poems and vendor’s cries to love poems and songs of longing. For example:

İreyhan eker misin

Bal ile şeker misin

Kız ben seni alırım

Kahrımı çeker misin

Do you sow sweet basil bright,

Are you honey, pure delight?

Girl, I’ll take you for my own

Will you love me through my plight?

Meanwhile, historical sources suggest that the Romanian

manea had four lines in an AABB rhyme scheme. The earliest transcription of such a

manea appears in folklorist Gheorghe Dem Teodorescu’s

Poesii Populare Române (Romanian Folk Poems, 1885), transcribed from a puppet show in which two Bucharest street vendors quarrel comically:

Iaurgiulŭ: Turcu estî, mă, și de unde vii?

Bragagiulŭ: (cântat pe aria unei manele)

Ah, aman, aman !

De la Giurgiu viŭ,

turcesce nu sciŭ;

para’n pungă iok,

mâncare de locŭ…

Yogurt vendor: You’re a Turk, eh, and where are you from?

Braga [fermented drink] vendor: (sung to the tune of a manea)

Ah, aman, aman!

From Giurgiu I come,

I know not the Turkish tongue;

In my bag I haven’t a penny,

Nor food have I any.

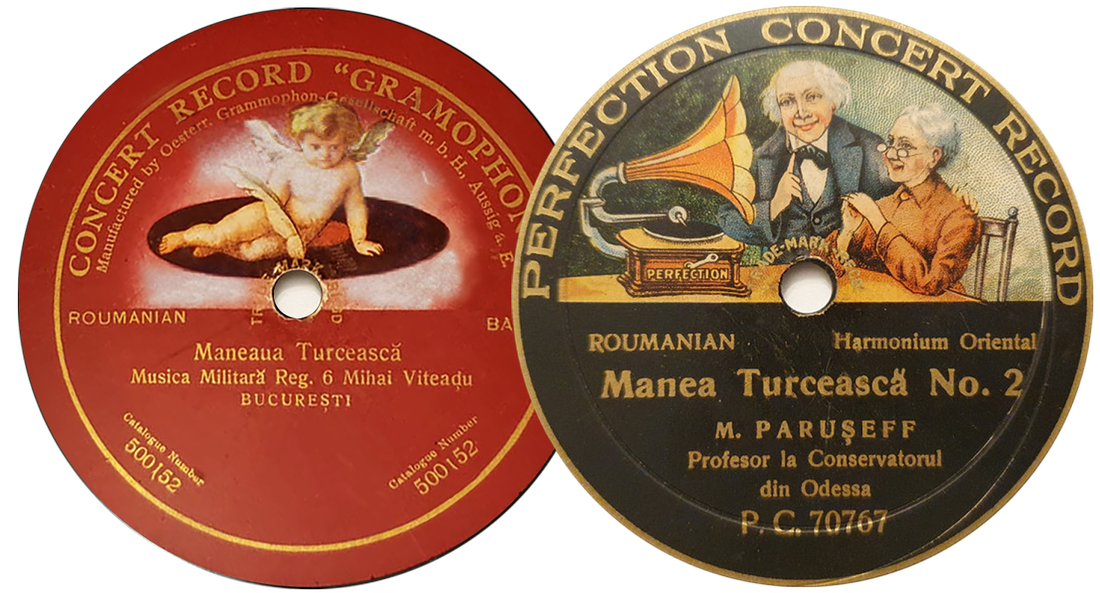

No known recordings of these early sung

manele exist, though an example of modern-day sung Turkish

mânîler can be found in

Ramazan mânisi—songs performed in the streets during Ramadan to wake observers for the pre-dawn meal.

Here, the drum serves not as rhythmic accompaniment but rather announces the singer’s presence and punctuates the stanzas of the

mânî.

How, then, did the

manea become associated with the belly dance rhythm we know today? As the older, non-metered vocal

manea faded from memory at the end of the nineteenth century, another Ottoman-inspired form was gaining popularity: the

turcească (“Turkish”)—a 4/4 rhythm with various forms equivalent to the Turkish

düyek, the Yiddish

terkisher, and the Turkish

sofyan. By the turn of the twentieth century, the word

manea had become so emblematic of Turkish folksong in the Romanian popular imagination that it was applied to pieces with the

turcească rhythm as well. Whether this was a misunderstanding, a product of the “folk process,” or clever marketing by musicians trading on the exotic allure of a foreign word, we will never know.

Norihiro Haruta.jpg)