French acoustician Vladimir Gavreau stumbled upon infrasound's destructive potential while running Marseille's CNRS mechanics lab. Steve Goodman calls him "a key hyperstitional figure"—someone whose reality became entangled with fiction, highlighting how science and imagination intertwine around acoustic weapons.

Gavreau built a 24-meter concrete-embedded organ pipe reproducing 7 Hz, then created an “acoustic laser” with seventy-four synchronized pipes of identical length. He claimed 7 Hz produced “unpleasant throbbing in the head” making “simple intellectual tasks impossible”, theorizing this matched the brain's alpha wave frequency associated with mental inactivity. His

“acoustic gun”—a hybrid organ pipe and Levavasseur whistle set in a 200-kilogram concrete block—allegedly generated 196 Hz at 160 dB. Gavreau and colleague Henri Saul, wearing ear protection, reported “painful resonance” where “everything inside us seemed to vibrate”. Gavreau called it “very nearly lethal”, claiming longer exposure would cause internal haemorrhaging, with the resonance sensation lasting three hours.

Modern scientists at the same institute doubt Gavreau's conclusions, noting his experiments haven't been replicated under proper conditions. Yet his legend spread beyond academia. William Burroughs told Crawdaddy magazine in 1973 that Gavreau possessed “an infrasound installation that he could turn on and kill everything within five miles”, wondering if borderline infrasound music could produce rhythms in audiences. Industrial band Throbbing Gristle later claimed use of infrasounds and ultrasounds during their concerts induced both orgasms and involuntary defecation.

Researchers Stanley Harris and Daniel Johnson

had already exposed men to 7 Hz at 142 dB for fifteen minutes without any drop in performance, dizziness, or confusion. This alone should make us skeptical of patents claiming "subliminal acoustic manipulation of nervous systems" using infrasonic frequencies. Broner

admits an infrasonic weapon might prove lethal at 174 dB, but the engineering realities are absurd. Even an ideal system would need a thousand times more power than a Saturn V rocket at liftoff, and the sound source would have to be 1,100 meters wide to work properly at just 250 meters distance. His verdict is blunt: military infrasound isn't practical. The report suggesting Gavreau's so-called “Trompette Marseillaise” could recreate Joshua's feat at Jericho's walls was pure wishful thinking.

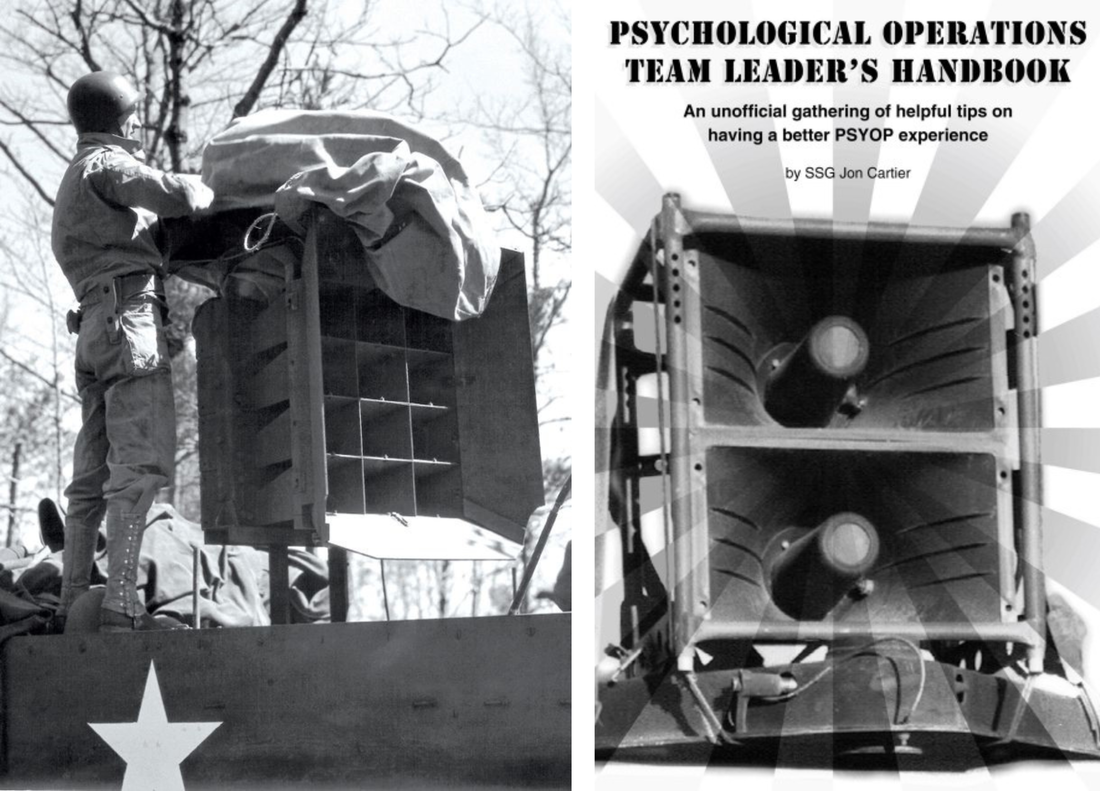

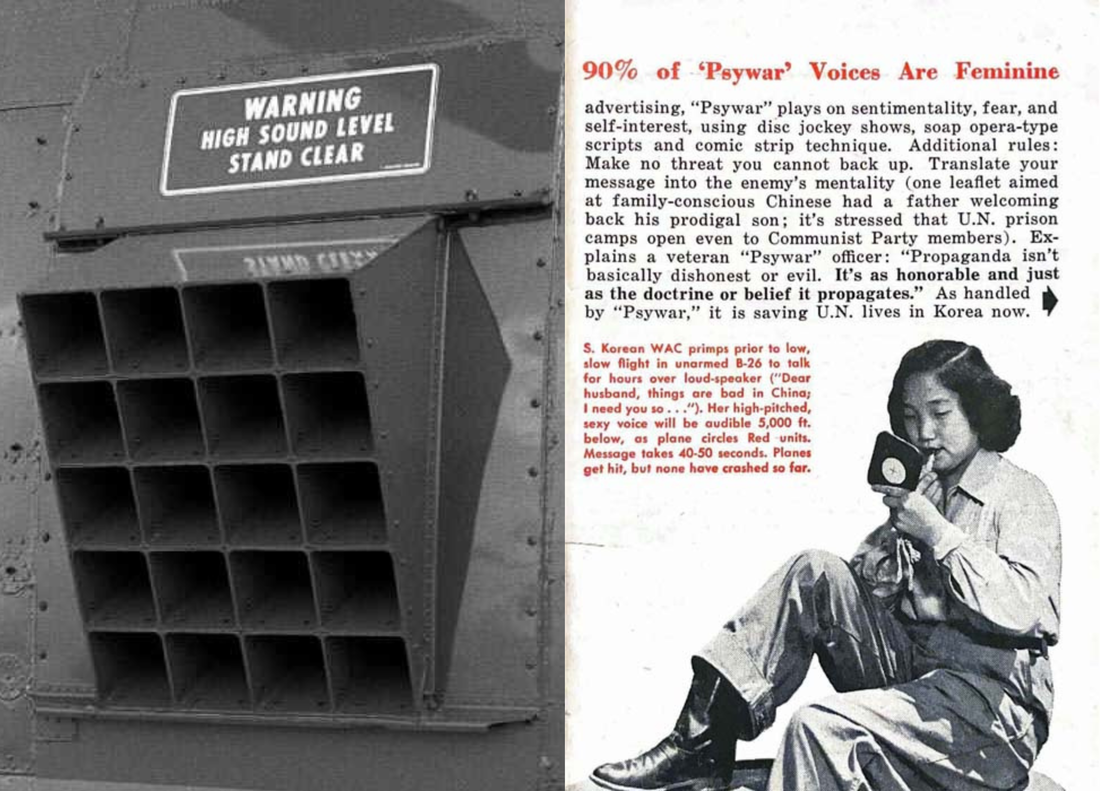

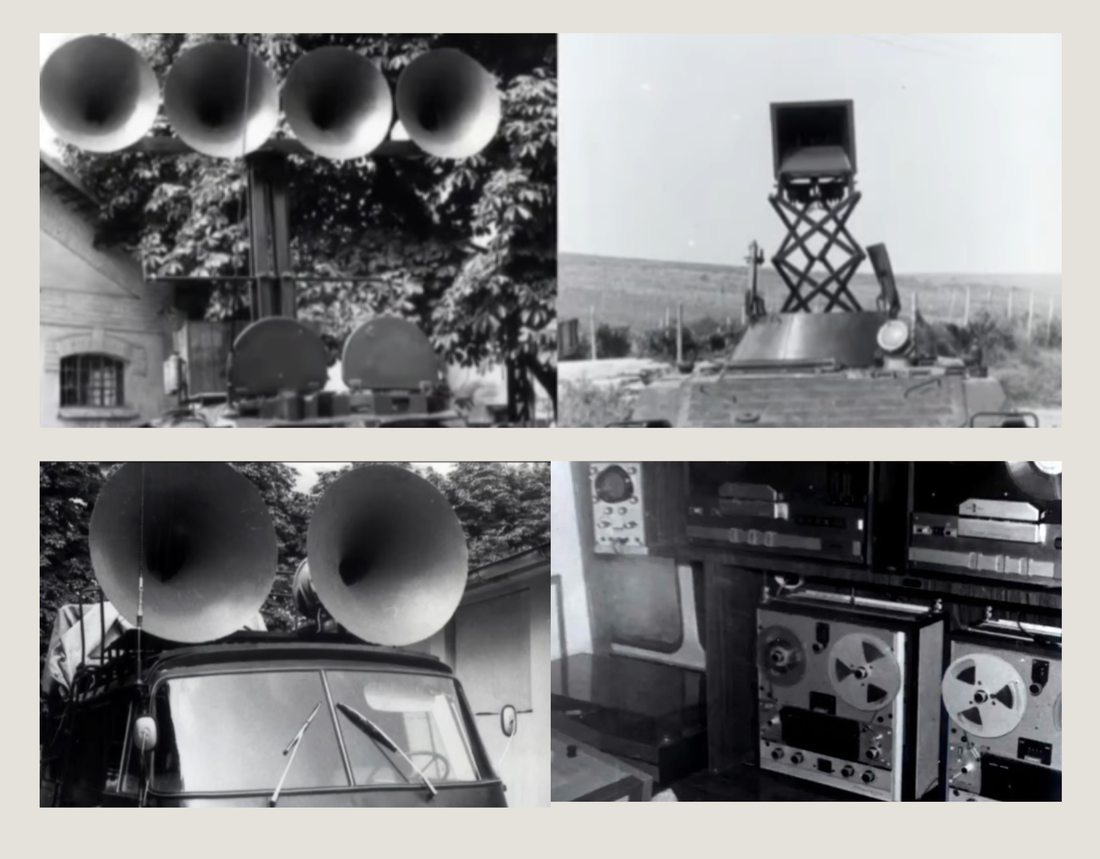

Sound as psychological warfare went beyond silence—it embraced its opposite: relentless, crushing noise. During the “war on terror”, interrogators turned music into a weapon, blasting it nonstop in detention centers and black sites. At Guantánamo and similar facilities, prisoners endured days or weeks of deafening sound in what soldiers cynically dubbed

the Disco.

The playlists weren't random. Interrogators carefully selected culturally offensive and psychologically brutal tracks—AC/DC, Metallica, and Drowning Pool mixed with Barney's saccharine I Love You”. The logic was calculated: heavy metal's aggressive distortion would feel alien and grating to Middle Eastern detainees, while children's songs would infantilize and humiliate grown men. One former prisoner described the mental breakdown: “you lose the plot, and it's very scary to think that you might go crazy because of all the music.”

When these torture playlists became public, the reaction was telling. Outrage mixed with dark comedy as commentators debated the “best songs for torture”—a response that trivialized real violence by turning it into entertainment. This wasn't accidental. The military's use of pop culture as torture weaponized the very products designed for pleasure, revealing the twisted relationship between entertainment and state violence. The same songs that filled dance floors could, with enough volume and repetition, shatter minds—a perfect “sonic assault” hiding in plain sight.

Music and the war machine are more entangled than at first sight. The British record company Decca pivoted smartly during WWII. Tasked by the Royal Air Force in 1940 with refining underwater acoustics to distinguish British vessels from German ones, it seized the opportunity to advance its recording technology. In the aftermath of WWII, EMI transformed and captured German research on Morse code analysis into the development of cassettes and tape recorders, fitting the Abbey Road Studios for the next quarter-century. In a remarkable piece of avant-garde music trivia, when Karlheinz Stockhausen began mixing his ground-breaking electronic composition “Kontakte” at Westdeutscher Rundfunk studios in Cologne between February 1958 and fall 1959, his pulse generators, amplifiers, band-pass filters, and oscillators were all made up of discarded US Army equipment.

The Theremin and its signature wailing sound evoking sci-fi worlds or moments of cinematic horror are results of a military lab work. In his early twenties, young physicist Leo Theremin joined the newly created Physical Technical Institute in Petrograd. After the 1917 October Revolution, the Soviet government tasked Theremin with researching proximity sensors. Building a device using electromagnetic waves to measure gas density and detect approaching objects, he accidentally made an instrument that produced a high whining sound. The instrument lacked military application. When Theremin returned to the Soviet Union in 1938, following an accomplished career, he was sent to a scientific gulag for 8 years to work for the KGB. Theremin's most notorious creation during that phase was the Buran, a hidden listening device that remained undetected for 7 years in the U.S. embassy in Moscow.