Written by:

Edited by:

Share article:

Also in this context the city finds itself with a new soundtrack as native sevdah artist Damir Imamović released Singer Of Tales, an album whose beauty and elegance matches that of the city itself. Sevdalinka is Bosnian folk music of great eloquence and meditation. It is rooted in Turkish culture from a time when Sarajevo was a major administrative centre for the Ottoman empire. Like any living music it is fluid and can be sculpted by the artist singing it – traditionalists might insist that it should be voice and saz (a long-necked lute) but since the end of the civil war following the dissolving of Yugoslavia wrecking carnage on the citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina sevdah has shape-shifted and taken on a new urgency.

The Amsterdam-based Bosniak producer Dragi Sestic discovered both Mostar Sevdah Reunion and Amira Medunjanin in the years following the end of the war and their sevdah fusions have won them international audiences. More recently, cross-dressing sevdah-electro singer Božo Vrećo has drawn comparisons with Bulgaria’s Azis and become something of a Balkan icon for gay and women’s rights.

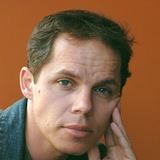

Imamović’s international profile is quieter than the aforementioned performers yet he has been working on his art for almost two decades. That said, he has performed from the US to China and Singer Of Tales, his seventh album, was recorded in Berlin with Joe Boyd and Andrea Goertler producing and Jerry Boys engineer (this trio previously helmed Saziso’s superb album of Albanian folk songs, At Least Wave Your Handkerchief At Me).

While the musicians joining Imamović are also gifted: Ivana Đurić (violin), Derya Türkan (kemenche) and Greg Cohen (double bass), all have remarkable pedigree. The dynamics of the musical interplay go way beyond language – only Imamović and Đurić speak Bosnian – and the resulting album is a 21st Century masterpiece. In the three months since the release, the album has been very well received, being at the top of several traditional music charts.

I first met Imamović several summers ago in Sarajevo and was impressed by both his music and winning personality. He had been scheduled to perform at the Barbican in London on May 1st, to promote Singer Of Tales but the Covid-19 pandemic ensured he stayed home.