…And what are we supposed to understand (or not) from this term?

Queer theory is a post-structuralist critical theory that emerged in the early 1990s out of the fields of queer studies and women's studies and includes both queer readings of texts and the theorisation of 'queerness' itself. Heavily influenced by the work of

Gloria E. Anzaldúa,

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick,

Judith Butler and

Laurent Berlant, queer theory builds both upon feminist challenges to the idea that gender is part of the essential self and upon gay/lesbian studies' close examination of the socially constructed nature of sexual acts and identities. Whereas gay/lesbian studies focused its inquiries into "natural" and "unnatural" behaviour with respect to homosexual behaviour, queer theory expands its focus to encompass any kind of sexual activity or identity that falls into normative and deviant categories. Queer focuses on mismatches between sex, gender and desire.

The idea that I have in mind is about what constitutes male-ness, female-ness and what constitutes “normal” are all socially constructed. It's just like your parents who tell you about what is wrong and what is right and all the stories when you are young. And then queer theory comes along and screws with your morals and your parents’ narratives.

Queer has been associated most prominently with lesbian and gay subjects, but analytic framework also includes such topics as cross-dressing, hermaphroditism, gender ambiguity and gender-corrective surgery. Queer theory's debunking of stable sexes, genders and sexualities develops out of the specifically lesbian and gay reworking of the post-structuralist figuring of identity as a constellation of multiple and unstable positions. Karl Ulrich's model, he understood homosexuality to be an intermediate condition, a 'third sex' that combined physiological aspects of both masculinity and femininity.

I want to create a small glossary to see how the genre is redefined. This is only a very personal idea:

Gender binary: Gender is a choice between male and female, based on gender identified at birth. Gender binary is limiting and problematic for those who do not identify with one category or another.

Gender fluid: a person whose identity or sexual expression is fluid from female to male palette or is another spot of gender spectrum.

Genderqueer: a person whose sexual identity is not masculine nor feminine, but is in some point which is beyond gender/or is a combination between genres.

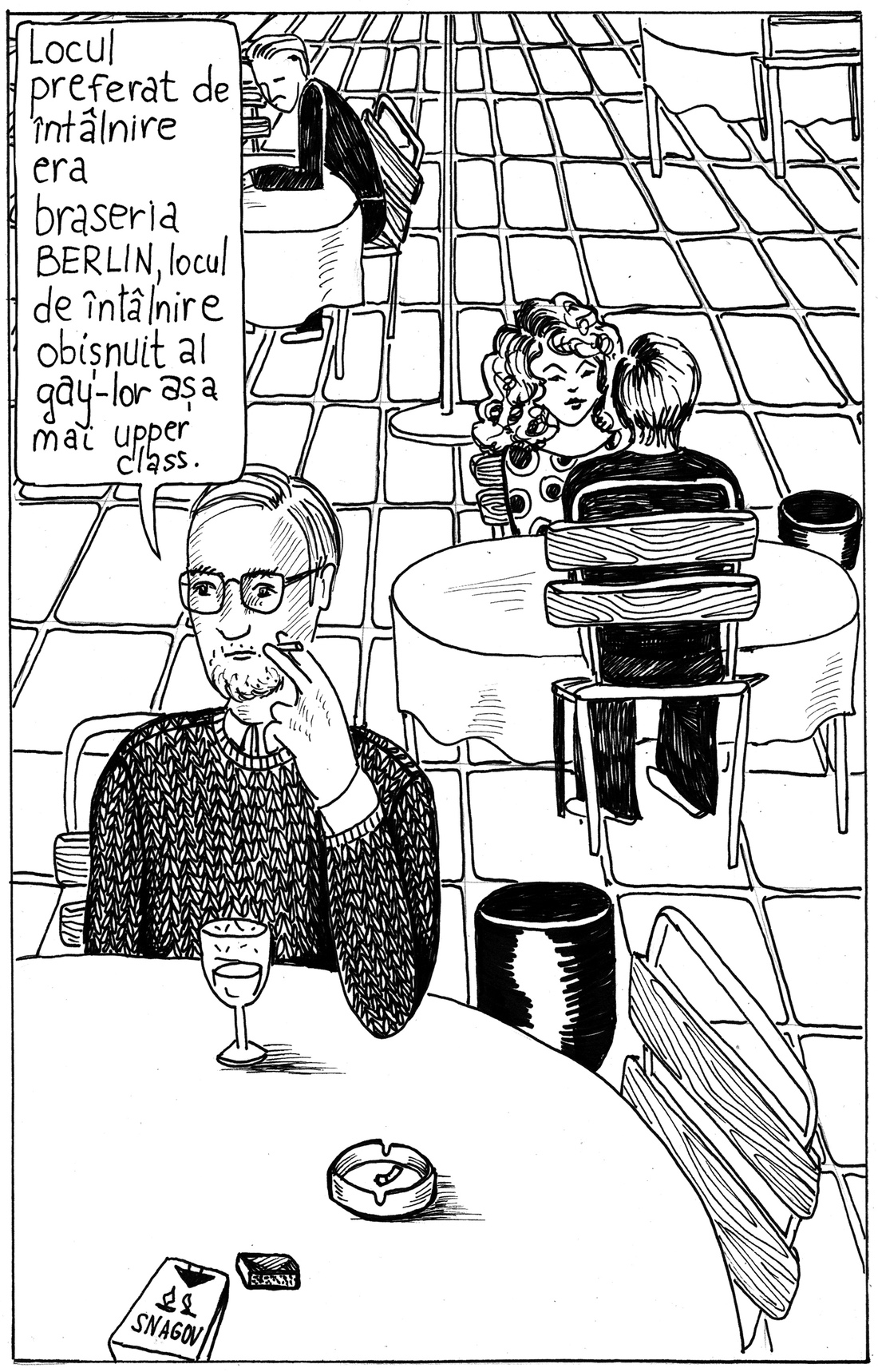

Queer is a product of specific cultural and theoretical pressures which increasingly structured debates (both within and outside the academy) about questions of lesbian and gay identity. Queer is by definition whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant. There is nothing in particular to which it necessarily refers. It is an identity without an essence. 'Queer' then, demarcates not a positivity but a positionally vis-à-vis the normative.

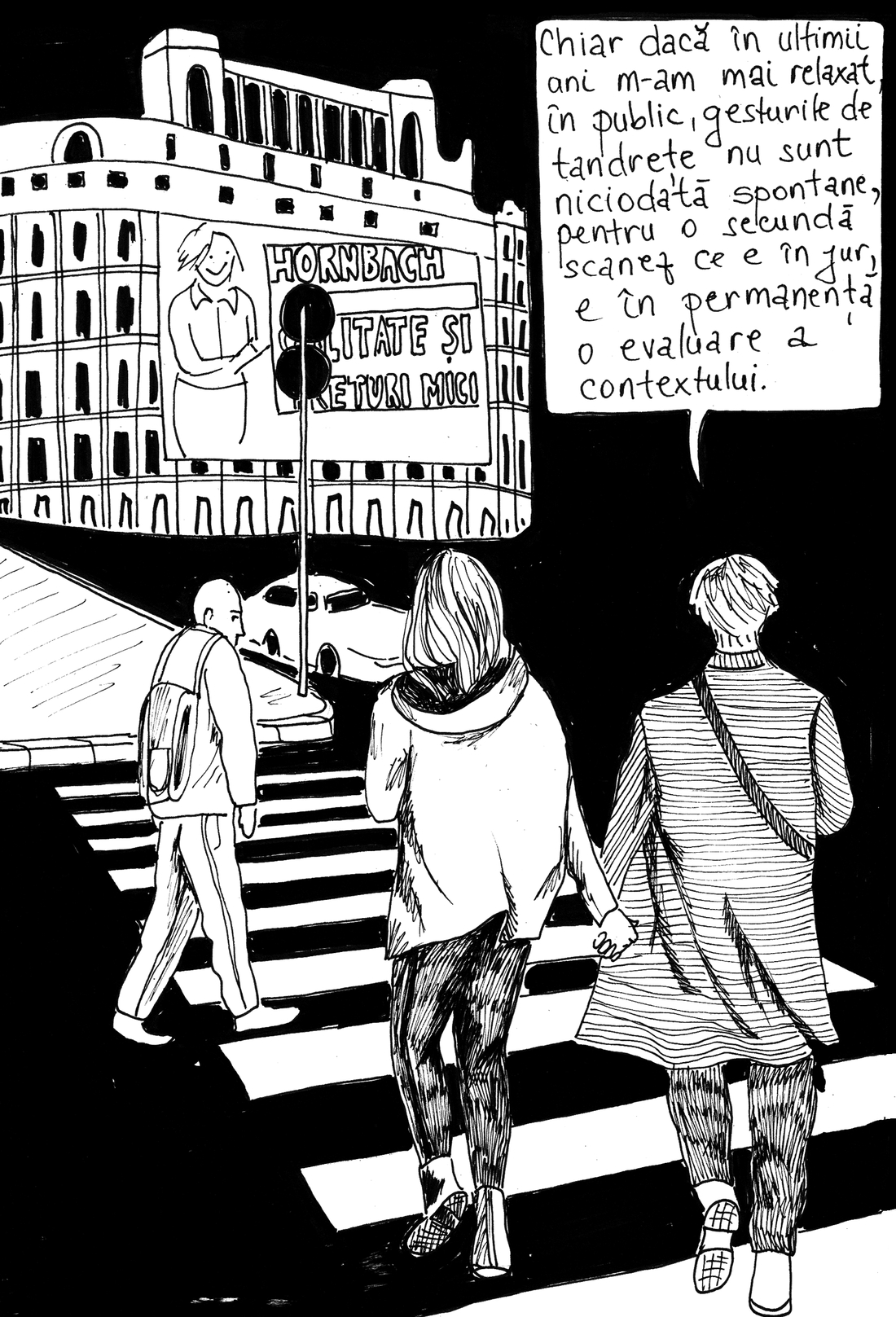

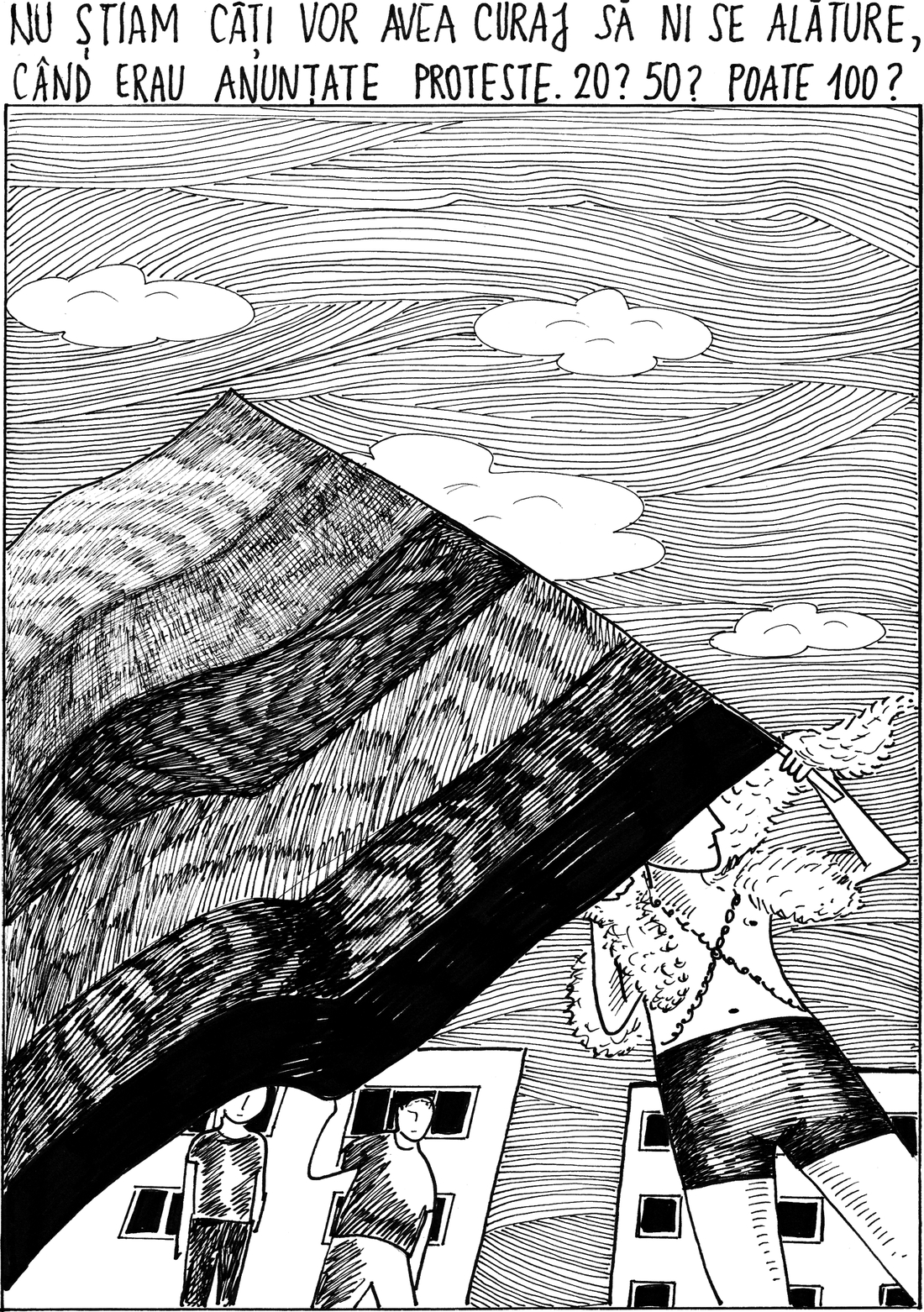

Queer is political. Queer is also personal. But in terms of cultural perspective, everything that is personal (or public) becomes political and gender discussion is a political strategy for disrupting the heteronormativity narrative - this is why the queer theory is all about breaking down norms and institutions, specially those who violently destroy the social normality of acceptance and integrations.

Queer theorist

Michael Warner attempts to provide a solid definition of a concept that typically circumvents categorical definitions: "Social reflection carried out in such a manner tends to be creative, fragmentary, and defensive, and leaves us perpetually at a disadvantage. And it is easy to be misled by the utopian claims advanced in support of particular tactics.

Queer theory was originally associated with radical gay politics of

ACT UP,

OutRage! and other groups which embraced "queer" as an identity label that pointed to a separatist, non-assimilationist politics. Queer theory developed out of an examination of perceived limitations in the traditional identity politics of recognition and self-identity. In particular, queer theorists identified processes of consolidation or stabilisation around some other identity labels (e.g. gay and lesbian); and construed queerness so as to resist this. Queer theory attempts to maintain a critique more than define a specific identity.

Acknowledging the inevitable violence of identity politics, and having no stake in its own ideology, queer is less an identity than a critique of identity. However, it is in no position to imagine itself outside the circuit of problems energised by identity politics. Instead of defending itself against those criticisms that its operations attract, queer allows those criticisms to shape its – for now unimaginable – future directions. The term will be revised, dispelled, rendered obsolete to the extent that it yields to the demands which resist the term precisely because of the exclusions by which it is mobilised. The mobilisation of queer foregrounds the conditions of political representation, its intentions and effects, its resistance to and recovery by the existing networks of power.

But the range and seriousness of the problems that are continually raised by queer practice indicate how much work remains to be done. Because the logic of the sexual order is so deeply embedded by now in an indescribably wide range of social institutions, and is embedded in the most standard accounts of the world, queer struggles aim not just at toleration or equal status but at challenging those institutions and accounts. The dawning realisation that themes of homophobia and heterosexism may be read in almost any document of our culture means that we are only beginning to have an idea of how widespread those institutions and accounts are”.

Queer theory's main project is exploring the contesting of the categorisation of gender and sexuality; identities are not fixed – they cannot be categorised and labeled – because identities consist of many varied components and that to categorise by one characteristic is wrong. Queer theory said that there is an interval between what a subject "does" (role-taking) and what a subject "is".