Part II: Modern Elegies

I arrived in Paris Wednesday morning, after a sleepless night and a 6 am flight to Beauvais Tille, also known as the bus stop airport. Porte Maillot, with its shuttles and cheap bus rides, brimming with immigrants and Asian backpackers was a much too painful déjà-vu. Only this time I wasn't headed to my 5th floor walkup with a terrace in Clichy, but to and a couple of nights on an air mattress in my friend's new apartment, still filled with moving boxes and lingering paint smell. Getting accustomed to the 10-degree temperature drop from Bucharest, all I could think about was sleep.

As I rushed towards the already familiar sight of L'Église Saint Merry, this catholic church by the Kandisnky fountain, right near IRCAM and Centre Pompidou, I was already back into my grumpy Paris self, cursing the crowds at Les Halles and sporting a permanent frown. Last time I was there back on a cold night in September, when John Butcher did a solo and Eliane Radigue presented one of her new acoustic, orchestra pieces.

There are three things you need to know about this church - it's extremely cold, the chairs are notoriously uncomfortable and the sound is always challenging because of its architecture. For the first time, I felt like Saint Merry found the perfect performance for the space in Ellen Fullman's Long String Instrument. I first saw a movie of this piece in a show at Le Plateau and I remember being greatly impressed by the physicality of the instrument.

Now, it was a question of scale - stepping into the empty space, with only a couple of people from the festival staff shuffling around preparing for the big night, the sight of this 30 meter long catwalk surrounded by strings that took over the entire nave was quite breathtaking. The entire installation was wrapped in traffic tape, an extra security measure for this robust yet delicate instrument. The resonating strings were held together by 15 large 35kg sand bags on each side.

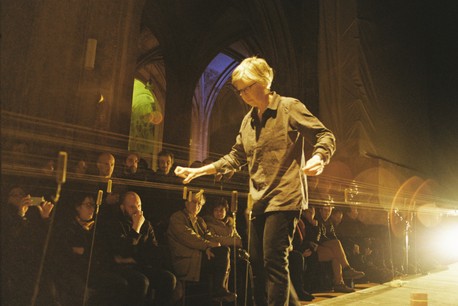

A fragile silhouette, not much taller than 1.60m, dressed in a nondescript black windbreaker and sneakers, was walking among the strings, making final adjustments. Composer Ellen Fullman was a particularly discreet presence, with her short white hair, tiny glasses and a gaze suggesting perpetual curiosity. Part of the wave of great minimalists, influenced by Alvin Lucier and Harry Partch, she is a lesser-known figure among the average contemporary classic music fan.

Just like Eliane Radigue in France, her incredibly innovative work has been marginalized until the last decade. This was to be her first performance in France and it was no surprise that Eliane Radigue, the other great lady of deep drones, was there to support her. The two together, chatting, made for an endearing sight and an important page in the history of modern music.

Later, at the communal table, I somehow ended up at the same end of the table as them; it was surprising how everyone from the staff was just going on about their dinner, while the two ladies were wrapped up in their own private bubble, sharing ideas about each other's work. The one thing that caught my ear was Ellen asking Eliane about her notation system, to which she replied that she didn't have one and had to explain to each performer how to play her pieces.

Returning to the church, I could see all the intricate series of numbers scattered across the wooden walkway, from sheets that looked like scores to numbers marked near the resonating wood boxes or the stones that were weighing down metallic clips onto the strings. I didn't know if I was looking at a Carl Andre/ Daniel Buren hybrid piece of sculpture or at a gigantic, gutted prepared piano.

Soon, the spots behind the seats and those between the rows started to fill; some younger kids were even sitting on the freezing church floor in front of the chairs. We were gearing up for a sold out evening, which, given Saint Merry's capacity, meant around 600 people. Then, the large stage lights went on; the tape was cut. The audience was growing restless in anticipation.

Ellen took to the stage and started gently tapping on the strings at the left end. The beginning was very low and subtle, certainly not enough to drown her out. My angry glaring certainly didn't help. Then, something changed. The whispering stopped. Everything pretty much stopped, for that matter, as Ellen's piece was slowly growing bigger and more resonant. Even the photographer stopped taking photos, as if embarrassed by the sound of his camera disturbing the silence of the piece. It was as if the entire audience was swept by this large wave of emotion, drowning everything in its way.

The metallic drones grew deeper and deeper as Ellen was walking across the platform, as if in a trance, like a shaman trying to control the fire of her vision. It sure was a strong beast to tame, this grandiose, unusual instrument.

If in the first couple of minutes people were still holding out their phones, documenting this strange sight, they quickly started to let go and patiently listen to the slow progression of the music. I don't think I ever heard the church audience as quiet as that night. There was a sort of collective concentration, a group focus that felt almost electric. The drones started getting deeper and deeper, evoking dark visions that were slowly growing darker.

I didn't even dare look at Ellen, although her small but stern fingers kept moving across the strings, barely 20 cm away from me at times. She was looking down, carefully following her notes. The atmosphere started to get darker; you could sense the thick layer of emotions she conjured. Everyone around me was frozen, possessed.

About five seats down from me on the opposite row there was this blonde woman, ducking between the passageways left between the seats. She was on her knees, looking up at Ellen, fist clenched under her chin. Her eyes were wide and moist and mouth vaguely agape. The composer kept her slow pacing up and down the catwalk and this lady's stare was following her every move.

The next time I looked at her, I could see the black smudging of her eyeliner giving her a hazy look. As the piece progressed, I was more and more fascinated by this woman, whose mascara started dripping by now. It's as if she was expressing a sort of ancestral suffering awakened by the music, in a sort of Madonna pose bearing all of our pain. Maybe she has just recently broke up with her boyfriend or was going to some other very personal drama; either way, the music sure struck a chord with her and there she was, full-on crying for all of us dry of tears. It was such a touching portrayal of this large, sad, beautiful music. By the end of the first piece, I must have seen at least three people barely holding back their tears.

Then, the music stopped. It took about 45 seconds for the last chords to finish resonating before the church broke into a frenetic applause. It was a cathartic moment, as if a heavy lead blanket had been suddenly lifted. I believe that if she kept going for even a few more minutes, we might have all ended up in tears.

Visibility uncomfortable by the overly enthused round of applause, Ellen muttered a quick 'Thank you' and rushed to the middle of the walkway to turn on a motor for her next piece. This was a much shorter and lighter effort, the constant movement on the string giving it an almost jolly undertone. Again, an explosion of applause and ''Bravos!''s followed. I think the composer was slightly startled by this utterly warm welcome and slightly annoyed for having her set interrupted.

She then placed herself at the left end of the catwalk, where the resonating boxes and loose ends of the strings were. She started rapidly pulling on them, building up an alert pace of higher tonalities. At first it looked like some kitten playing with the extra string hanging from the knitting basket and we weren’t even sure if she was playing or simply started undoing the installation. This roughly 5 minute piece has the much needed playfulness after the first long meditation. It almost felt like a hopeful glimmer of light that would help us get out of the dark world she has previously ushered us into.

Things moved quite quickly after that – the staff started moving the chairs, uncovering the sand underbelly holding together the whole apparatus. The transition was probably a little too abrupt but they were already behind schedule and there was no time to lose.

I felt like even if that was the only thing I got to hear during the festival, I would go home happy. As I went outside for some air, I almost couldn't fathom coming back and listening to more music. Ellen's piece was just that overwhelming. Even if you didn't enjoy it, it still had quite the impact. The whole experience was quite humbling.

I heard the sound engineer talk to some other guy afterwards describing it as ''heavy''. At the same time, especially after that first taste of returning to Paris and all the turbulences that ensued, it felt like the most appropriate thing one could listen to in those messy times; something that played on our fears and pain, exposing it into the music. Ellen's elegy had strangely specific undertones in her universality.