Written by:

Share article:

As an Iranian born to and brought up in a middle-class family, Persian poetry has been a consistent part of my daily life. In fact, this is the case with most Iranians; the everyday language is filled with poetic metaphors to describe not only the deepest, but sometimes the trivial incidents, emotions, and interactions. ‘Rose’ is a metaphor of love; ‘daffodil’ is the symbol of the eye; falling in love and being inebriated on wine are used interchangeably; the lips of the beloved are likened to spinel and ruby; and ‘jet’ stands for their black hair.

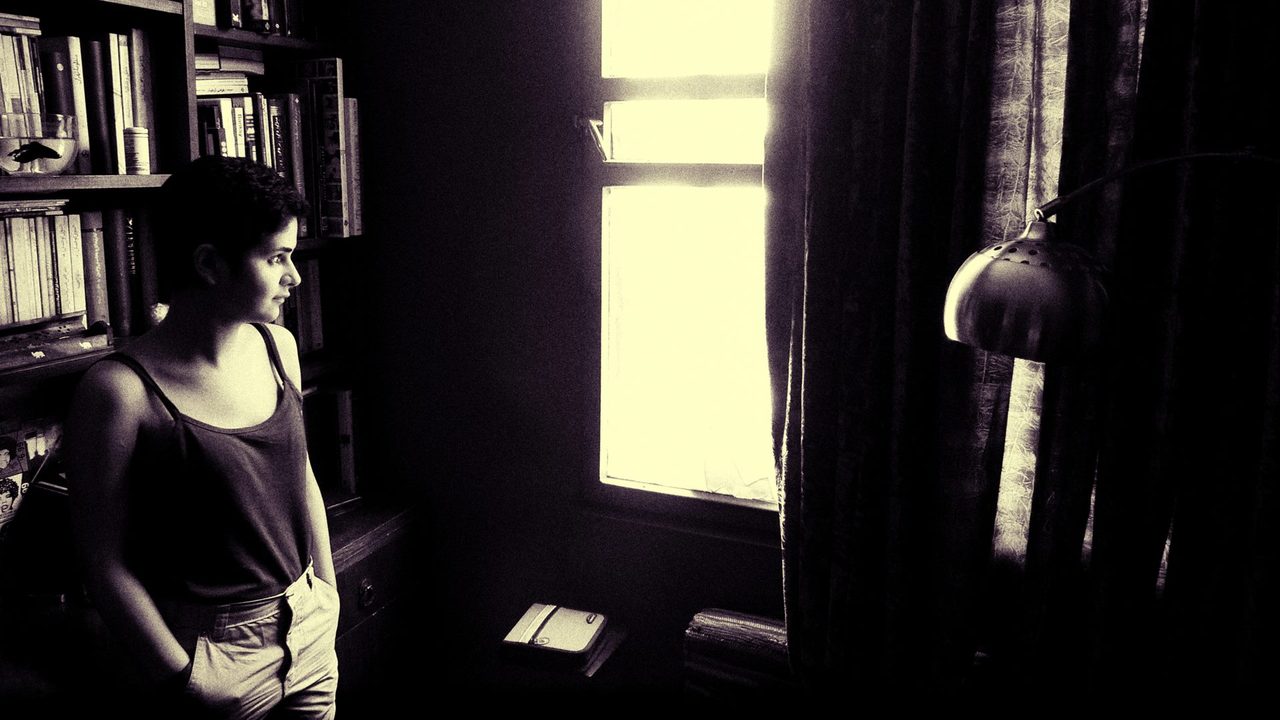

I remember my first encounter with Sohrab Sepehri's poetry. It was a hot, humid summer in the late 90s. I was 11, and we were on vacation in a small coastal town by the Caspian Sea. That year, we stayed at the home of a family friend with an impressive library of unique books. One day, after our daily stroll in the woods and swimming in the creek behind the house, while everyone else was having their siesta, I started shuffling through the library and came across an old paperback edition of a book entitled Hasht Ketaab, meaning ‘Eight Books’. It was a collection of works by the 20th-century poet and painter, Sohrab Sepehri. At first, it was disorienting to read the free, rhyme-less poems, influenced by the poetic style known as Nimaaee, coined by the renowned avant-garde Iranian poet, Nima Youshij. There was little to no trace of meter and rhyme as in Hafez, Rumi, Khayyam, Ferdowsi, Saadi's poetry. The recurring combinations of long and short syllables that give the reader a sense of stability and predictability, hence safety and soundness, were gone. I stumbled, limped, and sometimes slid through the lines, trying to latch on to "something", but it wasn't there…

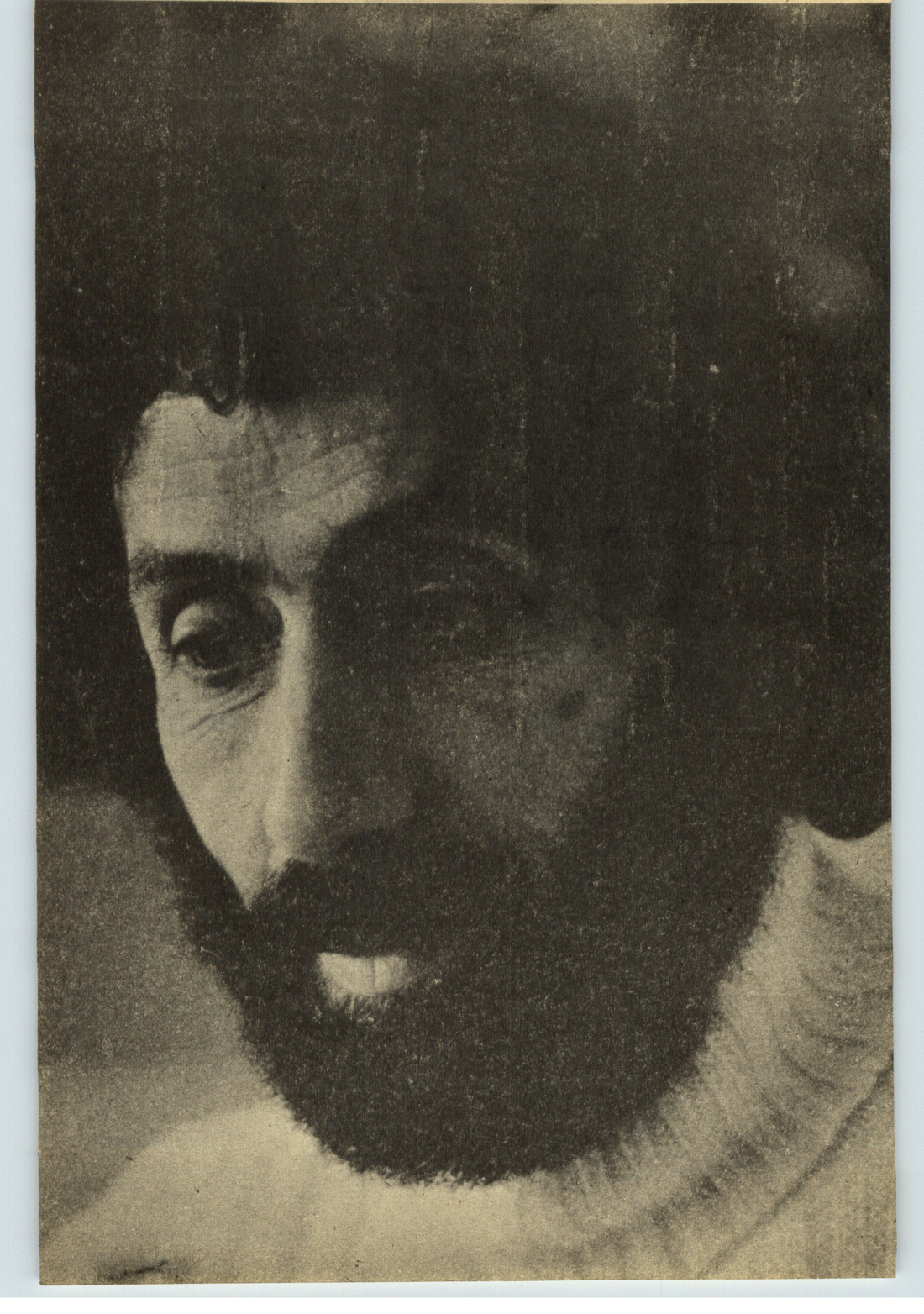

Sepehri is known for his affinity with Eastern philosophy, which manifested itself as a seemingly simple but highly symbolic language that transcends every phrase and image to something beyond its immediate meaning and effect. Despite his socially introverted personality, his approach to art and poetry was quite bold and adventurous. Sepehri was a trailblazer in modern Persian poetry and revolutionized its language, themes, and aesthetics. While his poetry may be less known to non-Persian-speaking audiences, his paintings are known to international artists, collectors, and auctions. Sepehri’s poetry continues to endure the passing time and transient poetic trends.

That afternoon marked the addition of Sepehri to the list of the poets that I had known and read. Still, it took his work some years to grow on me. I had to mature enough to appreciate his pure, innocent, and deeply personal and poetic language. After more than twenty years since that day, I often read his works with astonishment and joy. Sepehri’s pictorial, multi-layered, and deep language continues to have an undeniably deep impact on my perspective on music-making.