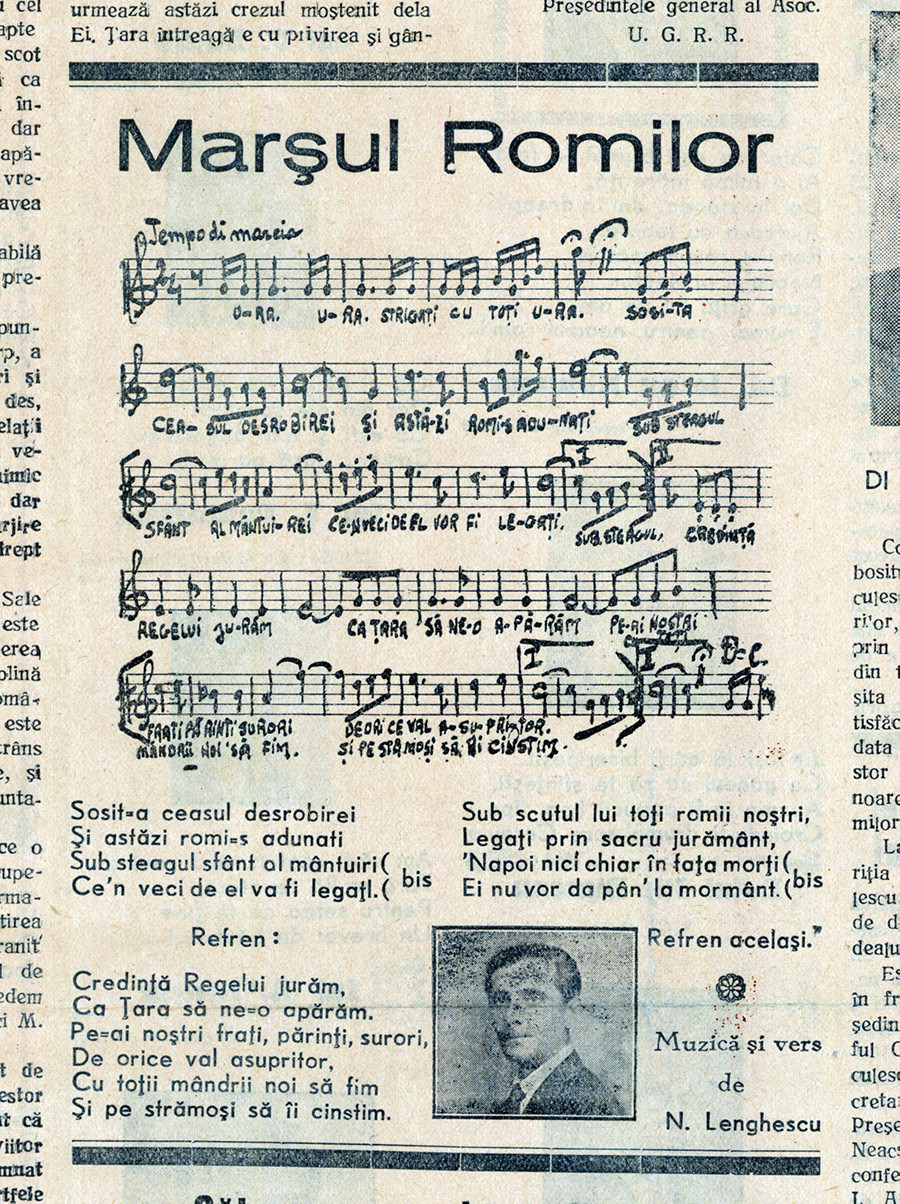

“The time for liberation has come / and today the Roma have gathered / under the holy flag of salvation / to which they shall always be bound” -- "March of the Roma" composed by Romani musician Nicolae Lenghescu-Cley, published in "Glasul Romilor" (Voice of the Roma) 14th ed. (1940).

Lăutari had enjoyed a newfound prominence in the interwar period, with virtuoso soloists such as Grigoraș Dinicu, Fănică Luca, and Zavaidoc representing Romania on stages throughout Western Europe. The image of muzica lăutărească as central to Romanian culture was further solidified by the work of ethnic Romanian performers like Maria Tănase, Ioana Radu, and Gică Petrescu, who collaborated with lăutari throughout their careers. A movement for Romani emancipation (and further assimilation) began in Bucharest in 1933, led by successful Romani businessmen and musicians, and for a brief period before the war, the Roma minority and its language (through newspapers such as Glasul Romilor) became slightly more visible.

After the war, the Romani political organizations of the interwar period were disbanded, and the new Soviet-aligned communist government effectively omitted the Roma minority from its vision of Romania, ignoring their very existence. Roma, including lăutari, were expected to assimilate into the working class, and explicit public expressions of Romani identity were sparse. Two rare exceptions were the Electrecord EPs entitled “Muzică populară țigănească” (Gypsy folk music) published in 1959 and 1963 that featured songs in the Romani language (Rromanes) by lăutari Fănică Vișan and Dona Dumitru Siminică.

Nicolae Ceaușescu’s 24-year reign (1965-1989), referred to in state propaganda at the time as the “Golden Epoch” (Epoca de Aur), brought lăutari ever further into the limelight, while at the same time obscuring their Romani identity.

Aurel Ioniță: On New Year’s Eve, everyone would turn on their TVs to listen to muzica lăutărească played by Gabi Luncă and Ion Onoriu, Romica Puceanu with the Gore Brothers, Dona Siminică, and Fărâmiță Lambru. They were all Gypsies! But there was no policy for supporting the Gypsy language or culture like in Yugoslavia or Bulgaria where they were selling records in Roma language. In Romania there was a different policy [toward Roma] but there was still a need for this [Romani] culture because there were many Gypsies, so they needed to show a bit of Gypsy music. But look, they had to sing in Romanian so that it would be accepted by the majority. In the communist period Gypsies didn’t exist; there were only “Germans, Hungarians, and other nationalities” – that’s what Ceaușescu said.

Ceaușescu’s policies artificially ended unemployment by forcing every citizen over the age of 18 to have a salaried job. This also essentially outlawed traditional lăutărie, since lăutari performed at weddings and baptisms as self-employed freelancers and typically did not report their income or pay taxes.

Marian Mirea: Most lăutari had no other job, so when this order came that everyone needed to be employed […] the wedding musicians went and got hired at various plants and factories to have a job and benefits.

Țagoi: In Ceaușescu’s time, if you didn’t want to get a job, they’d throw you in jail. I worked in Bucharest at a warehouse for clothing materials, leather and such. It was hard work, lifting these huge rolls and putting them on shelves. Of course my boss knew I was a lăutar when she hired me. There were lots of us [lăutari] employed in jobs like that. Whenever I had to play for a wedding on a Monday, I’d come to work in the morning at eight and tell my boss, and she’d mark me as present for the day and let me leave. “Go around through the back and jump the fence, Sandu!” she’d say.

Beginning in the 1960s and intensifying after 1976 with the inception of the “Cântarea României” (Song to Romania) national festival, orchestras performing folk music (muzica populară) played an important role in the creation and maintenance of Romanian national identity. Every locality was encouraged to participate, and in many cases local lăutari formed the core of these “amateur” ensembles.

Marian Mirea: Under communism, most of the musicians in folk orchestras were lăutari, so [ethnic] Romanians were in the minority. I’ve seen cases where a Romanian would come with a flute or harmonica or something and the lăutari would say “Hey Gadjo, what are you doing here? What do you know how to play?” The lăutari were playing weddings all week and could really tear it up on their instruments, and the Romanians just couldn’t compete; they were employed during the week at factories and didn’t have other opportunities to play. Eventually the lăutari would accept them because, well, they had to. That was the policy. It was easier for a Romanian to get into these Gypsy-dominated musical ensembles than for a Gypsy to get into a Romanian-dominated ensemble like a symphony orchestra or pop orchestra.

In the village of Clejani in Giurgiu county, the situation was a bit different. With such a large community of talented local lăutari, there was not enough room for everyone on stage, so a selection had to be made to form the official “Taraful din Clejani”. Renowned lăutar violinist Ion Albeșteanu was hired to lead the band, and helped shape the supergroup that would later become Taraf de Haïdouks.

Țagoi: There were 27 of us in the taraf, Taraful din Clejani. Of course there were other lăutari in town, but we were the 27 best. There were 5-6 violins, 3 or 4 țambal players, 3 or 4 accordions, a contrabass, a cobză. […] When we had rehearsals, we all got special notes from the mayor’s office that we’d take to our jobs so they’d give us paid time off.

In ’87, [folklorist] Speranța Rădulescu took me with my accordion, [singer] Cacurică, [țimbalist] Petrică, [singer] Ion Boșorogu (Manole), [violinist] Neacșu, and [flautist] Fluirici to Bucharest for a recording session with a Frenchman. I remember it was cold in the hotel. We didn’t know how to talk with the Frenchman, so we used hand signals. When Speranța asked us what we wanted, I said “we don’t want to die fools. If this record comes out good, ask him to send us to play there [in France]. She talked with him “bla bla bla” and he said “OK”. We didn’t know what OK meant, but he was saying “OK, OK, OK”. And Speranța told us the answer was yes, if the record came out good.

Then in 1990, right after the revolution, [Belgian music producer] Stéphane [Karo] had heard the recording we’d made and he came looking for us. “Where’s Neacșu, Neacșu, Neacșu?” It was winter and there was a lot of snow. He came to our house and Dad [Nicolae Neacșu] was here in this room with me and Manole. When [Karo] heard us playing live for the first time, he said “Ouh là là, ouh là là… want to make a taraf?” So we went with him to Belgium to make a disc, and he called us “Taraf de Haiduc”.

The rest, as they say, was history. By 2001, Taraf de Haïdouks had released four commercial albums with the Belgian-based World Music label Crammed Discs and was touring worldwide. Țagoi had left the band 1992 following a dispute with Karo, but his father Nicolae Neacșu stayed on as the face of the band, appearing (together with Țagoi and his son Marinel) in the 1993 Toni Gatlif pseudo-documentary Latcho Drom.

In 1998, the new Berlin-based talent agency Asphalt Tango Production joined the scene with their own “discovery” from rural Romania – brass band Fanfare Ciocârlia from the Moldavian village of Zece Prăjini, releasing three hit albums in just four years. Both agencies were scouting for new talent among lăutari at a time when Romania was undergoing a tumultuous post-revolution period of economic turmoil and rampant corruption. Aurel Ioniță, then a young violinist growing up in a Bucharest mahala, was picked up by Asphalt Tango for a tour with his band Rom Bengale (“Rogue Roma”) in 1998.

Marin “Țagoi” Sandu (b. 1950) is a vocalist and accordionist from the town of Clejani in southern Romania. He was part of the initial lineup of Taraf de Haïdouks together with his father Nicolae “Culae” Neacșu. Țagoi has performed with numerous other ensembles in recent years, including Nea Vasile și Taraful de la Mârșa and Bahto Delo Delo. He and his wife Marcela have four sons and three daughters, all of whom received a musical education in the home.

Marin “Țagoi” Sandu (b. 1950) is a vocalist and accordionist from the town of Clejani in southern Romania. He was part of the initial lineup of Taraf de Haïdouks together with his father Nicolae “Culae” Neacșu. Țagoi has performed with numerous other ensembles in recent years, including Nea Vasile și Taraful de la Mârșa and Bahto Delo Delo. He and his wife Marcela have four sons and three daughters, all of whom received a musical education in the home. Marian Mirea (b. 1958) is a violinist and bassist, a fourth-generation lăutar and son of the celebrated conductor Constantin Mirea. A native of Bucharest, he is classically trained and has been a member of numerous ensembles including the Romanian Folklore Ensemble “Ciocîrlia”, The National Radio Orchestra of Romania, Orchestra Gheorghe Zamfir, and Ștefan Bucur Ensemble, and has recorded with lăutari legends such as Gabi Luncă, Ion Onoriu, Toni Iordache, Marcel Budală, and Vasile Pandelescu.

Marian Mirea (b. 1958) is a violinist and bassist, a fourth-generation lăutar and son of the celebrated conductor Constantin Mirea. A native of Bucharest, he is classically trained and has been a member of numerous ensembles including the Romanian Folklore Ensemble “Ciocîrlia”, The National Radio Orchestra of Romania, Orchestra Gheorghe Zamfir, and Ștefan Bucur Ensemble, and has recorded with lăutari legends such as Gabi Luncă, Ion Onoriu, Toni Iordache, Marcel Budală, and Vasile Pandelescu. Aurel Ioniță (b. 1967) is a violinist, composer, bandleader and founder of the lăutar-Balkan-Romani folk-pop band Mahala Raï Banda. Raised in a family of lăutari from Clejani, he began his career in Bucharest with the experimental folk band Rom Bengale and went on to work as an arranger for Fanfare Ciocârlia and Kočani Orkestar before founding Mahala Raï Banda in 2004. He has toured worldwide and performed with international acts including Esma Redžepova, Šaban Bajaramović, Balkan Beat Box, Shantel, Goran Bregović, Mariah Carey, and Scorpions.

Aurel Ioniță (b. 1967) is a violinist, composer, bandleader and founder of the lăutar-Balkan-Romani folk-pop band Mahala Raï Banda. Raised in a family of lăutari from Clejani, he began his career in Bucharest with the experimental folk band Rom Bengale and went on to work as an arranger for Fanfare Ciocârlia and Kočani Orkestar before founding Mahala Raï Banda in 2004. He has toured worldwide and performed with international acts including Esma Redžepova, Šaban Bajaramović, Balkan Beat Box, Shantel, Goran Bregović, Mariah Carey, and Scorpions.