On the same trip in 2009, when I met

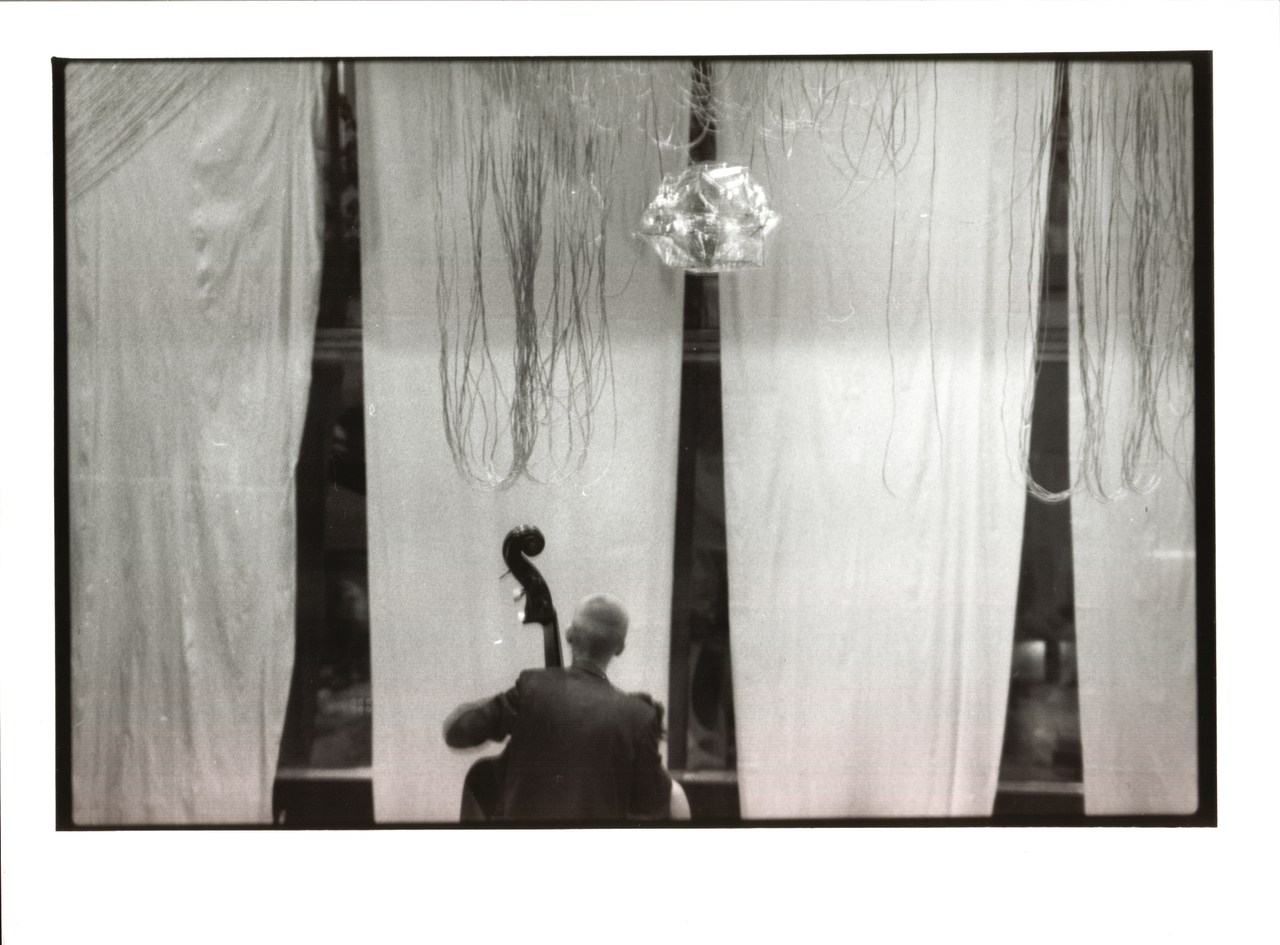

Szilárd for the first time, I also met his mother and father. And just as I did with Szilárd’s music, I fell in love with his mom’s visual work, absolutely instantly. (As for his father, I also fell in love with his homemade schnapps, but that’s a different story.) She works in a multiplicity of media: printmaking (monotypes/ drypoint), montage, felt, ceramics, etc. The sheer range is impressive, but what’s really spectacular is how recognizable her hand is in everything she touches, no matter what medium it might be in or what subject she might be investigating.

Her work incorporates a lot of abstraction, yes and always, but also landscape, architecture and animals: ladders, moons, trellises, earthen crags, fish. The question of what is “real” and what is “abstract” isn’t relevant when looking at her work: she creates seamless combinations of the two: how we see things, and how it feels to see them. Possibly even how it feels to be seen.

Erzsébet Mezei was born in January of 1947 in Székelykeve, a Hungarian village settled in the late nineteenth century by Bukovinians in what is now the southern end of Vojvodina. Her ancestors arrived into this region of the Lower Danube in 1883, bringing with them a way of life that treasured singing and storytelling. She earned a degree from a Teacher Training College in Novi Sad in the Faculty of Fine Arts, and enjoyed a career teaching art to school children.

In 1991 she had her first exhibition in Novi Sad, and three of her pieces won the Katona József competition. She has continued to receive prizes, including the Takt in 1996, the Forum Award for Fine Arts in 1999, the Pro Urbe in 2009 and, most recently, the Nagyapati Kukac Peter Prize in 2015, the most important prize for fine art by Hungarians in Vojvodina.

watercolor and graphite

When I look at her work I see shadowy spaces, splintered wood, breathing threads, stark earth, brightnesses glowing and softened, indefinite distances, scribbled weather, leaf coffins, abyss meters…her work makes me think: poetically, geographically, politically, psychologically. Ivan Obseiger described her work as if it brought “binoculars to see beyond the ephemeral quality of everyday life,” reminding us that “joy is not an antipode to sorrow and discomfort but a companion.” Her stark burnt colors and morphing forms balance physical attraction with psychic challenge: metallics bleed “in bright dusk,” to use Pál Léphaft’s apt phrase.

I sat down with Erzsébet and Szilárd, our translator, at her kitchen table, to talk with her about her work and its place in her life.

Andrew Choate: Why did you start making visual art?

Erzsébet Mezei: I don’t think of myself as an artist, only time will tell. But I have always made things with my hands. When I finished high school, I wanted to be an architect. But in school I changed my mind and decided to study to be a professor of fine arts. And after graduating, I started to teach. During this time I didn’t make a lot of my own work - the things I made were small, like prizes for the kids I was teaching in school. I also made clothes for Szilárd and his sister. Once they were teenagers, and grown up, I started making graphic works - monotype and drypoint prints.

I had my first exhibition in 1990, showing these graphic works.

Andrew Choate: How did you start working in felt?

Erzsébet Mezei: I was teaching a ceramics workshop for professionals, and next door was a group doing felt, so I decided to try it. Like I said, I always liked working with my hands, and this was a new way to use my hands.

Andrew Choate: Does Szilárd’s music have an influence on you, and if so, when did that start?

Erzsébet Mezei: The first concert I saw him play, when he was really his own person, was in 1990, I could really feel his music, and that did coincide with the arrival of my own work in my life. But it was a lot of things - his sister Kinga was also growing up, and she started acting, and that influenced me also. The inspiration was going both ways, all three ways - Szilárd began composing music to be performed in public and Kinga was performing in public, it gave me new energy. And I started making posters for his shows.

I should also say that my father was a trumpet player in a brass band. And he also composed music. Sadly his scores were lost in a fire when our house burned. He composed polkas.

Andrew Choate:How do you feel about Szilárd’s music?

Erzsébet Mezei: Even though it is new, it seems very recognizable to me.

Andrew Choate: One of the similarities I find in your two arts is how distinctive you both are: when I see an image by you, I know it is you; when I hear a note of Szilárd, I know it is him. Is your art connected to this place?

Erzsébet Mezei: Yes, through the theme of ground, the grass, the animals, the sheep. I don’t have to paint those things directly to feel that they are near and in my work. This place is not a concept, it is just the way it is, natural. Colors from the earth, as if you cut into the earth - those are my colors, the colors of this region. Here there is no direct light, unlike the seaside, here we have more pastels and peasant nature.

Andrew Choate: What motivates you to continue?

Erzsébet Mezei: I can´t imagine how to live otherwise. I’m always finding something new; you can't ever reach oneself in time. It's a lifestyle of making things. Like a jazz musician. It's a form of life and also a profession at the same time.

--

*photo credits:

szilardmezei.net