Written by:

Share article:

An adventure

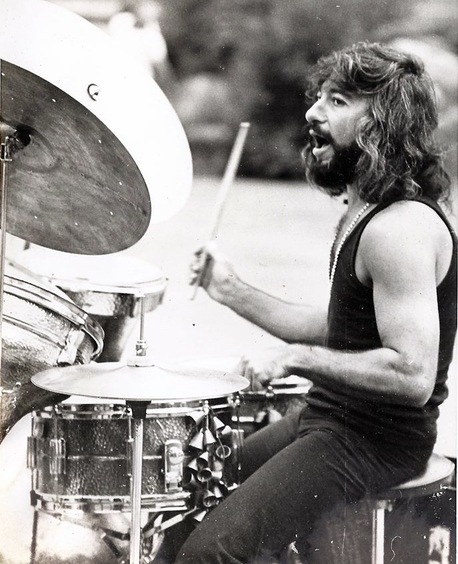

He’s an extremely respected musician worldwide and one of Turkish most famous Jazz musicians, although his adventure with music broke many conventional boundaries throughout years.

Okay was born in Istanbul in 1939. After he studied at the State Conservatoire of Classical Music in Ankara, he started to perform in several programs and shows, accompanying dance music groups in Turkey. In 1967, he joined Ulvi Temel’s group and appeared in some of the most outstanding music halls of Europe. A few years later he relocated to Sweden, after meeting Don Cherry and trumpeter Maffy Falay.

Later on he formed the group Xaba (a crucial part of his musical career) with the skilled bassist Johnny Dyani and the South African trumpeter Mongezi Feza. They got released on the Scandinavian record label Sonet.

With his Swedish Turkish Jazz group called Oriental Wind, Okay Temiz moved further into multi-cultural music and reached a very appealing synthesis by blending European musical instruments like the violin, saxophone, flute, clarinet, bass and piano with Turkish instruments such as zurna, ney, kaval, ud, saz, gayda and sipsi. For a short while, his mother Naciye Temiz also joined the group and accompanied in some of the performances they gave in Sweden. Oriental Wind was originally made up of renowned musicians like pianist Bobo Stensson, bassist Palle Danielson, saxophonist Lennart Aberg, and the master of ney and gayda, Hacı Tekbilek.

Okay’s own ravenous energy and endless passion for exploring the unknown, added to his long time musical experience led him to involve in numerous projects. He appeared in more than 350 festivals and took stage at about 3000 concerts in Europe, America and India. He recorded tons of albums and was involved in much collaboration with different musicians and jazz players from Europe, but also from the United States.

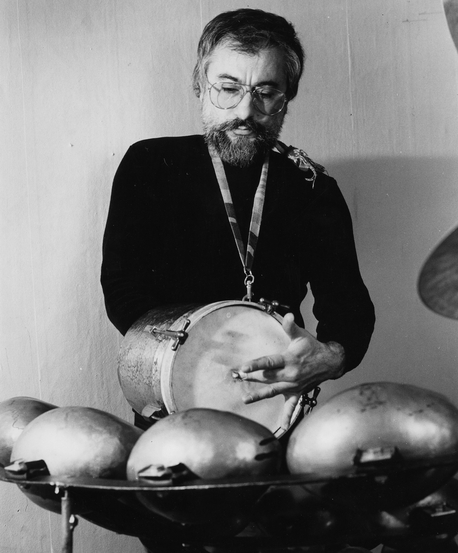

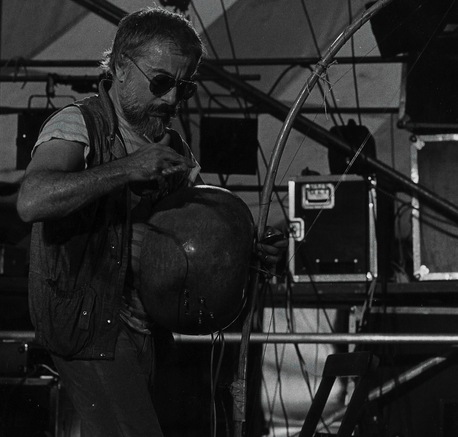

He came to know, listened to and worked together with top musicians who have mastered the rhythms of Africa, South America and India, in the meanwhile learning how to make and play their instruments like the quicca, berimbau, finger piano and talking drum. He has a wide collection of self-made ethnic and electronic instruments including the hand-made copper drums, Magic Pyramid and Artemiz, which he has made of camel and sheep bells.

Okay still continues his mission of spreading multi-cultural music to wider audiences through the uncountable experiences he has gained over the years.

We had the chance to talk via Skype with Okay Temiz, as he played for this year’s Europalia festival with a Belgium band called La Fanfare du Belgistan, on three different occasions: in Brussels (at Ancienne Belgique), Köln (at Stadtgarten) and Utrecht (during the Le Guess Who? Festival).

La Fanfare du Belgistan is a group of Belgium musicians featuring Jérémie Mosseray (tapan, percussion), Manu Loriaux (bass, percussion, sousafoon, synth), Manuel Roland (alto sax, gitaar, percussion), Tom Manoury (soprano sax, euphonium, percussive), Carlo Strazzante (frame-drums, derbouka, qarqaba), Quentin Manfroy (flute, percussion) and Grégoire Tirtiaux (bariton sax & tenor, percussion).