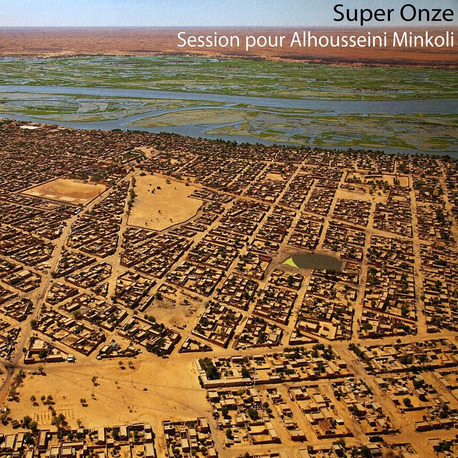

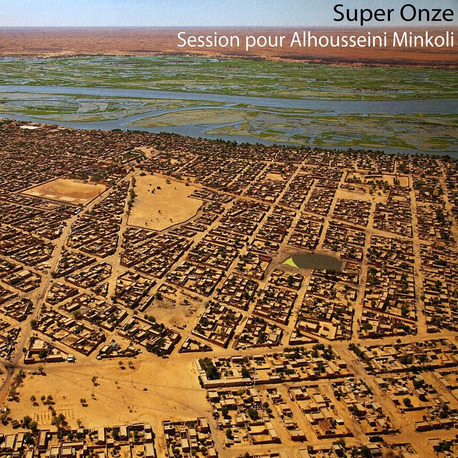

Alhousseini Minkoli was a rich tailor, soray, living in Gao, and a lover of takamba music. Recorded in Gao, Northern Mali, 1994

Super Onze de Gao was founded in the early 1980s by

Haziz Toure,

Asaalya Samake and

Agita Moussa Maiga, who became the group’s first president. All three were Songhai men from Gao. In the venerable tradition of so many West African music ensembles, Super Onze was created in order to entertain at community celebrations, preserve traditions, propagate culture and create a kind of ‘club’ or community organization which could support the needs and nurture the talents of its members. In other words, it was more than just a ‘band’ in the European sense of the word. The founding members are still alive, but now it’s the next generation that fills the active roles in the group. That’s another advantage of their typically African orchestral structure. It doesn’t depend on any individual or person for its survival, and can thus better cope with the passing of time.

Initially Super Onze de Gao played in their own homes, a few times a month and especially on Fridays, the day of prayer and rest in the Muslim week. From the beginning they concentrated strictly on the takamba style, and were soon a popular feature of local weddings and festivities. In 1985 they gave their first ‘official’ non-festive concert, at an election gathering in Gao.

Super Onze’s leading ngoni player is

Yehia Mbala Samake, son of Asaalya Samake. Yehia comes from a caste of Songhai blacksmiths. The role of blacksmiths in Songhai and Touareg society is very complex and very important. They belong to an endogamous group, which means you can only be born a blacksmith, you cannot become one. Until recently they were responsible for making almost everything necessary for nomadic or sedentary existence: tents, swords, spears, camel saddles, leather bags and cushions, padlocks, cooking utensils and, most importantly, jewelry. They still make jewelry and many other artifacts. But the role of the blacksmith has never been confined to artisanal manual labour. They’re also storytellers and guardians of family histories and lineages. They’re often called upon to negotiate between two rival clans, and to arrange marriages. And it’s their duty to play music at feasts and festivities. As such, their role has many affinities with that of the Manding or Bamana griot.

Super Onze members on this cassette: Yehia Mballa Samake - ngoni / kurbu; Douma Maiga - 2nd ngoni / kurbu; Aliou Saloum Yattara - calabash; Mohamed Kala - calabash.

Follow Super Onze de Gao on

facebook and

bandcamp.

*with passages taken from

Super Onze de Gao - Champions of the Niger Bend by

Andy Morgan, with kind permission from the author.