Rye Lane, where Gents Hairdressers stood just off, had once been one of South London’s most celebrated shopping streets but bomb damage and white flight – many English Peckhamites shifted to Kent and Essex in the latter decades of the last century – meant the big department stores closed and the Lane became a hub for small West Indian, African and Asian businesses. Across the Peckham Road the North Peckham Estate was built in the early 1970s, this concrete monolith standing as the UK’s largest social housing project. With its concrete walkways above streets linking different sections, the North Peckham Estate soon became one of the most deprived residential areas in Western Europe. Vandalism, graffiti, arson attacks, burglaries, robberies and muggings were commonplace, and the area became an archetypal London sink estate.

I was living in a tower block estate just opposite the North Peckham Estate on 27 November 2000 when police and ambulance sirens screeched up the road and into the estate: what they found was the lifeless body of Damilola Taylor, a 10-year old Nigerian boy who had been stabbed in the thigh by a teenage gang on his way home from school. This made both national and international headlines and emphasised Peckham as a cesspit of gang violence and social deprivation. Around this time I was asked on a BBC radio show about Peckham and could only think of two local positives against all the bad news: the rapper Giggs and the footballer Rio Ferdinand.

Paradoxically, Taylor’s death came as Peckham was beginning to change: Nigerians had settled here in large numbers – so much so that the neighbourhood would get the nickname “Little Lagos” (Star Wars actor John Boyega is one of such) – as were East Europeans: I noticed Polish and Romanian shops opening to cater for these new residents. The North Peckham Estate was already being demolished when Damilola died, replaced with new, low-rise council housing alongside government investment in making Peckham a more hospitable place to live (an award winning library was one of the first fruits of such – Damilola had visited the newly opened building minutes before heading towards home and his savage death).

By 2010 Peckham was officially being gentrified: a deserted car park in the centre of Peckham, long marked for demolition, drew international attention when Frank’s Bar, an innovative bar/arts space, opened on its top floor over summer. The remarkable views across London this offered – alongside the very chic presentation (sculptures and contemporary minimalist music performances were part of the bar package) - attracted in a breed of hipsters who had never before considered setting foot in south east London. As many in London media fit this demographic, Peckham was suddenly “happening”.

A selection of new bars, cafes, restaurants, art galleries and record shops opened and Peckham quickly went from being largely silent at night (once Rye Lane’s traders had shut) to abuzz with drunken youths rushing between bars and clubs. Being chic and offering cheaper housing than much of London also attracted people who, a few years prior, would not have considered settling in Peckham. In 2020, Peckham is both an epicentre of Black Britain – its population remains over 50% Afro-Caribbean/African - and an outlet for new businesses and youth culture. Inevitably, property prices have soared and there is sometimes a sourness evident towards the gentrifiers. Poverty and violent crime remain high but so does community pride, a sense that this is an exciting, multicultural place to live, somewhere where people rub along and respect one another.

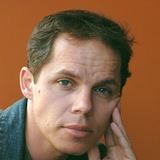

I imagine Andrew has gently embraced the excitement of the “new” Peckham while being firmly rooted in the old. He’s certainly seen this neighbourhood change greatly over the 55 years he has stood behind his chair and cut the locals’ hair. Yet unlike some elders he doesn’t bemoan the passing of the old days and the old ways. Instead, he remains positive towards the community, happy to have been able to serve for so many decades.

“I opened at 6.30 AM every day except Sunday – and I worked a half day on Wednesday,” he told me. “I enjoyed coming to work, seeing my regulars, meeting new people, treating everyone with respect and kindness and learning of their lives. Being a Rye Lane barber has been a huge part of my life and, a year ago, I would not have imagined I’d be retiring. But things change and its my time to stop working and spend more time with the grandchildren.”

He then shows me a commemorative road sign that Southwark council have presented to him: on one side it reads ATWELL ROAD SE15 1965 – 2020 and on the other “To Andrew and Steve Have a happy retirement From all your friends at Southwark Council”. Andrew smiles his gentle smile and I imagine this unimagined gift meant a huge amount to him. As does all the visitors packing into his shop. I look around this tiny space with its surviving red barber chair and think of the thousands and thousands of hours Andrew has spent standing behind it, cutting hair, noting changes of fashion in hair and clothes, in slang and accent, this barber to the people of Peckham, cutting and styling then sweeping up afterwards. A rough calculation suggests he likely spent in the region of 150,000 working hours here. And today Sotiris Andreou still stands tall, has a firm handshake, a twinkle in his eye and a grace to his smile. Bless this wonderful barber!

One thing I’m sure of is this: Peckham will miss our favourite Cypriot. His gentleness and warmth and the sharp haircuts that always left you feeling smarter, fresher, once you stepped out of his chair. Now, does anyone have a suggestion for a new barber? No recommendations over £10, thanks.

--

*This article is part of the project Music & Conversations in the Attic, co-financed by AFCN.